Christine Hamlett-Williams has been a subcontracted dining employee at AU for 34 years. Currently a cashier and a union shop steward, she sits most days behind the register at the mini P.O.D. Market in Mary Graydon Center. At 67, Hamlett-Williams wants to retire, but like other longtime dining employees, meager pension benefits over three decades have deprived her of this option.

Hamlett-Williams said she can’t afford to live on Social Security benefits. Her current pension fund, she said, amounts to about $13,000 before taxes.

An Eagle investigation has found at least six longtime subcontracted employees in similar situations. A 76-year-old dining worker with AU since 1966 had $8,000 in a pension fund when she withdrew some of it five years ago. “I got bills to pay,” that worker said, who hopes to retire in two years. “But I feel like if I’m able, why not keep on working?”

With AU’s dining and housekeeping services, contractors come and go, but workers often stay. New contracts with new companies may mean different benefits for those workers. Since the 1980s, the University has had three different dining contractors, with the longest serving being Marriott Corporation from 1981 to 2001. (After a merger in 1998, the company was known as Sodexho-Marriott for the remainder of its time at AU.) During the Marriott years, workers and workers’ rights activists allege some dining employees stopped receiving full pension benefits. At least 13 current food service workers have been employed since the Marriott era.

Unlike Hamlett-Williams, some longtime workers don’t even know how much money is in their pension funds, like one 77-year-old dining employee who started working in 1973. “I can’t retire,” that worker said. “I gotta be doing something.” Another dining worker at the school since 1981, who also asked to not be named, wasn’t sure how much was in her pension fund.

This story originally appeared as the cover story of the printed Dec. 4, 2015 special edition of The Eagle.

Workers attribute the lack of information to limited communication from their current union, Unite Here Local 23, and to the dining contractors that have shuffled in and out as their employers. In the 1980s under Marriott, workers were represented by Local 32, then later by Unite Here Local 25. In 2009, Local 25 redefined its oversight and Unite Here Local 23 was established, the chapter that currently represents AU dining workers.

“The only problem with the union is that they talk to some workers more than they talk to other workers,” said Julian Bloom, a junior and president of AU Student Worker Alliance. “That is an issue, because some workers don’t necessarily know the status of their retirement fund or whether they are considered full time or part time and how to pay union dues accordingly, so there are some issues of communication.”

Vincent Harkins, assistant vice president of facilities management for the Office of Finance and Treasurer, wrote in an email that his office “would not share contract documents as those are proprietary and would not be fair to share unless the contractor themselves would share with others.” Representatives of Unite Here Local 23 declined to comment for the article.

Director of Auxiliary Services Charles Smith also said that the University did not have copies of archival contracts. In a statement to The Eagle, he said, “We value the work of the food service employees every day and their contribution to the AU community. Please keep in mind these are employees of Aramark, and they are represented by a local food service workers’ union. The benefits they receive are determined by a collective bargaining agreement which AU does not participate in.”

"Instead of having [McCabe] locked up, ask us, 'What are you asking for?' Don't let this next generation end up in the same shoes we're in. It's time to make a change."

– Christine Hamlett-Williams

During contract negotiations in 1990 between Marriott and Local 32, the union that represented dining workers at the time, employees voiced concerns over their lack of benefits and hoped a new deal would improve the situation. “Right now, we don’t have any retirement benefits,” Beverly White, a then-30-year dining employee, told The Eagle in a September 1990 article. “Hopefully, we can get some with the new contract.”

That new contract, however, still lacked retirement benefits. According to a copy of the contract signed in January 1991 between Marriott and Local 32, the document never mentions the word “retirement” or “pension.”

Students filter in and out of P.O.D. during the lunch hour blitz on Friday, Oct. 30, buying their meals du jour, usually chips and a sandwich. On the job, Hamlett-Williams looks past the negatives. Many students know her by name, ask her about life and remember to say “thank you.”

She’s quick to remind students to get their money’s worth. “You’re paying for it,” she tells a student who forgets he can grab a bag of chips along with his sandwich and drink for one meal swipe. To her right lay two open mini-bibles on the table, worn and coffee stained, that she reads in her off time.

At 33, Hamlett-Williams needed a job. When she began working under contractor Marriott in 1981, officials told her she would get benefits comparable to University employees, she said, including aid such as free or reduced tuition, pension fund contributions and health care. She recalled that her first paychecks came from the University directly, despite the fact that a subcontractor was in place. But since the late 1980s, workers have not received tuition benefits, and many did not begin receiving pension benefits until 2001, when Bon Appetit took over dining services from Marriott-Sodexho.

Several longtime employees who can’t afford to retire said Marriott treated them well on the surface. For Christmas, workers were often gifted hams, turkeys, shrimp, or steak and pies. If employees had worked for 25 years, Marriott provided them with gift cards to stay in a hotel for a three-day weekend. “Marriott was the best,” said one of the workers who wished to be anonymous. Hamlett-Williams agrees that the gifts were nice but said she wished the company offered better financial support as well.

“That was nice,” Hamlett-Williams said of the Christmas gifts, “but they didn’t give us benefits to help us today.”

Christine Hamlett-Williams tells President Neil Kerwin and other top University officials about her pension situation at a Nov. 18 town hall (Nadia Palacios/The Eagle).

Without taking a close look at her job contract when she was hired — details of which are fuzzy to her, over 30 years later — “I just took what they said,” Hamlett-Williams said. “I believed in my heart if I worked for the University, that I would be treated right.”

The current food services contractor, Aramark, contributes $1.05 for each employee who works 20 or more hours per week, not exceeding 40 hours, to the Local 23 Employers’ Benefit Fund and Pension Fund, according to a copy of the latest contract.

Student activist Carlos Vera, who founded the Exploited Wonk campaign last year advocating for the rights of Aramark workers, said he doesn’t think it’s Aramark’s responsibility to make up for the pension money that Marriott never gave. He thinks AU will eventually pay for those workers’ retirement. “It’s ultimately [up to] the University,” Vera said, “this was happening under [their] nose.”

He also wants the University to offer contracted workers education benefits — like the ability for workers and their relatives to take classes for free or with reduced costs.

When asked if there are any plans for the University to reimburse workers who did not receive pensions, the Auxiliary Services director, Charles Smith, replied in an email, “I have no specific information regarding this question.”

Concern over workers’ benefits exploded on campus following the arrest of former professor Jim McCabe on Oct. 14. Images of police escorting McCabe out of the Terrace Dining Room, where he was handing out fliers advocating for dining workers, spread on social media and were briefly taped across campus walls.

“My phone blew up,” recalls Vera, who was in California when he heard McCabe was arrested. Vera said he received a lot of social media attention campaigning for workers’ rights last semester, yet it never became a huge news story. “In some ways [the arrest] helped spread our message.”

McCabe’s arrest drew attention to the issue from leaders around campus and from student advocacy groups. Student Worker Alliance members said meeting attendance swelled. Candidates for Undergraduate Senate released advocacy plans addressing the issue.

“I can’t retire. I gotta be doing something.”

– A 77-year-old food services employee who has worked at AU since 1977.

The Faculty Senate is also currently examining McCabe’s claims after professor Mary Gray presented a letter at Senate's Nov. 4 meeting with signatures from 40 professors.

“What strikes my emotions is that when [McCabe] found out about our pensions, he knew what was going on and he said it should have never happened. The University should have looked out to us, the workers,” Hamlett-Williams said. McCabe has advocated for workers like Hamlett-Williams on his website.

Three weeks after McCabe’s arrest, Aramark restored work hours for a group of dining hall workers whose hours were cut earlier in the semester. Student leaders met with AU Director of Dining Ken Chadwick behind closed doors shortly after the announcement. Undergraduate Senator Will Mascaro, who attended the meeting, said Chadwick told students the activism gave him leverage to ask his bosses to restore the workers’ hours.

“Chadwick is an ally,” Mascaro said. “I think he is in a difficult position. He works for a multibillion-dollar company that is likely trying to cut costs wherever possible. But I think he also recognizes that there is an issue with the way workers are treated, and he is trying to work with students to address our concerns.”

Chadwick declined to be interviewed for this story.

Hamlett-Williams wants the University to meet with workers like her who have worked decades but can’t afford to retire.

“Instead of having [McCabe] locked up, ask us, ‘What are you asking for?’” Hamlett-Williams said. “Don’t let this next generation end up in the same shoes we’re in. It’s time to make a change.”

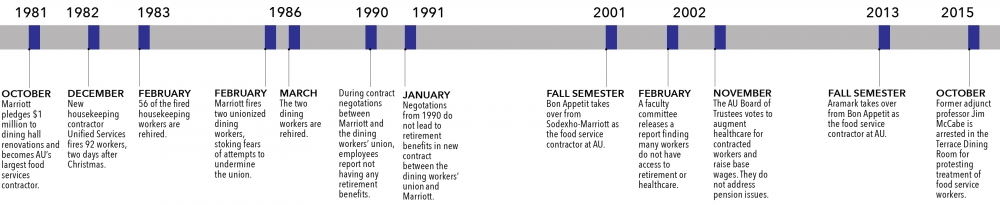

History of dining contracting at AU

Click on image for larger version (graphic: Cuneyt Dil/The Eagle. Source: The University library archives and The Eagle archives).

Under the Ronald Reagan administration in the 1980s, labor force and union representation underwent significant transformation, a trend that visibly touched AU. Universities across the U.S., including AU, began contracting services such as housekeeping and dining in efforts to improve efficiency and cut costs.

In a statement to the University community in 1983 about a switch to cleaning contractors, the administration wrote: “Why does one go to contract cleaning? First, it gives guaranteed level of cleaning throughout an institution or business. Second, it costs less. By using a contract cleaning firm, we will be saving more than $250,000 annually — that’s $5,000 per week.”

In October 1981, AU started contracting with Marriott to oversee all dining services.

The University had previously contracted with smaller companies which oversaw parts of dining services. In exchange for total control of all food services on campus, Marriott promised million-dollar renovations and offered flexible meal plans that were cheaper than the previous contractor’s, The Eagle reported that year.

Former AU vice president for Business and Fiscal Affairs, Jack McKinley, said that when Marriott agreed to spend a million dollars on renovations, the company blocked out any other food service provider that might have worked with the University.

"Right now, we don’t have any retirement benefits. Hopefully, we can get some with the new contract."

– Beverly White, a then-30-year dining employee, told The Eagle in a September 1990 article.

“Yes it is a monopoly,” McKinley told The Eagle in 1981. “If I spent a million dollars on renovations, I’d want some guarantee I’d be the only kid on the block.”

Shortly following the dining services switch to Marriott, AU also began subcontracting housekeeping services. Unlike in dining services, the University had no history of outsourcing the hiring and management of housekeeping workers.

The decision to subcontract housekeeping services built tension between workers and contractors. In December 1982, two days after Christmas, 92 housekeeping employees were fired during the transition to the new contractor, Unified Services. Students and professors protested the firing in front of the home of former University President Richard Berendzen and held teach-ins about workers’ rights.

“We wanted to ensure that staff on campus had their rights protected,” School of International Service professor Abdul Said said in an interview. Said was involved in the teach-ins and has worked at AU since 1957.

The dining service worker who has been at AU since 1981 remembers participating in the protests on campus when the housekeeping workers were fired. Following continued protests and negotiations with Local 25, the Hotel & Restaurant Employees Union that oversaw housekeeping workers then, Unified Services agreed to rehire most of the workers on Feb. 25, 1983. Of the 92 workers who were fired, 56 returned to AU, but under a very different contract than they had as direct University employees. The 56 workers returned to a full year of severance benefits, including former wages, health and life insurance, pension programs and tuition benefits.

This agreement existed for a year. Then, Unified Services reverted back to a standard wage contract, with payments of $4 an hour.

The one benefit that continued for workers under Unified was tuition waivers. Donald Triezenberg, the former vice president for development and planning, told The Eagle in 1983 that tuition remission or waivers were not a problem during negotiations with the workers’ union.

“We had no problem with that,” Triezenberg said then. “Education, after all, is our business.”

Contracting issues continued, but spread beyond housekeeping. In 1986, relations between Marriott and union dining service workers also grew strained. Following the firing of two employees in February 1986, unionized dining employees became concerned that Marriott management was attempting to eliminate union workers and replace them with non-union employees, The Eagle reported.

In March 1986, Marriott rehired the two workers.

Student worker advocates protest on the steps of the Mary Graydon Center on Oct. 30 (Zach Ewell/The Eagle).

When Marriott began in 1981, the University created University Student Services, Inc., a legal entity owned by the school. The formation of USSI was required because Marriott’s corporate structure did not allow it to hire unionized workers directly, according to Vice Provost for Academic Administration Violeta Ettle.

In order to become AU’s dining contractor, Marriott had to allow the union to remain in existence at AU. Betty Miles, a former shop steward and union representative, told The Eagle in 1986, “We are the only Marriott location that has a union.” Workers at this time had a separate pension plan and health insurance plan managed by the union. They did not get tuition remission, according to Ettle.

“One of the requirements to be hired was to join the union,” one worker said.

One longtime worker recalled that during the Marriott years, a representative from USSI under Marriott would come and talk with workers about changes or updates in contracts. When the Marriott contract ended, she said she no longer saw those employees and does not know the details of her current contract.

In the early 2000s, former University President Benjamin Ladner called for a new faculty committee to explore working conditions for contracted workers. The group, called the Living Wage Project Team, was chaired by John Willoughby, a professor of economics in College of Arts and Sciences. The final report, issued in February 2002, recommended implementing living wage salaries, as well as comparable healthcare, pension, education and tuition benefits.

The report found that employees with low hourly wages were unable to afford health care premiums or were entirely without insurance. If the University implemented employment benefits comparable to what faculty members had, the group found contracted workers would receive 5 percent of the minimum wage they earn to a pension fund, along with adjustments to healthcare, which the University would contribute $180 per worker at minimum wage.

The Board of Trustees rejected the full report, according to Willoughby. The board enacted an across-the-board $11-an-hour wage, lower than the LWPT’s suggestion of $12.58, and reinstated health benefits for contract workers in November 2002, according to an Eagle report from the time. The change did not include retirement benefits.

“There have been periodic controversies of worker conditions,” Willoughby said. “The issues are not really new if you have been here for a while.”

Though the issues may not be new, some workers who were hired at the beginning of the Marriott era, including Hamlett-Williams, face the final phase of their lives knowing that all the years of controversy have left them without financial security.

“My time is limited. I know I can’t do another 35 years, or probably not five years more,” Hamlett-Williams said. “I am going to work as long as I can, but health issues and other issues is going to be too much. But I would like to see a change and support the younger people who given it their all.”

At her station at P.O.D. Market, Hamlett-Williams’ Bible was open to a page in Corinthians. As she read, a line jumped out: “We live by what we believe, not by what we can see.”

“I am going by faith," she said, "not by circumstance."