Correction appended.

When Ariel Michaelson, a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences, arrives on campus each morning, she has trouble finding a parking spot. She drives to school because she cannot carry her books in the short walk to campus from her house. If it didn’t jeopardize her attendance grades, she would stay home when she doesn’t feel well, she said.

“I have a class at night. I’m in pain and so exhausted after a long day,” Michaelson said. “But if I can’t get to class, I’ll fail because of attendance.”

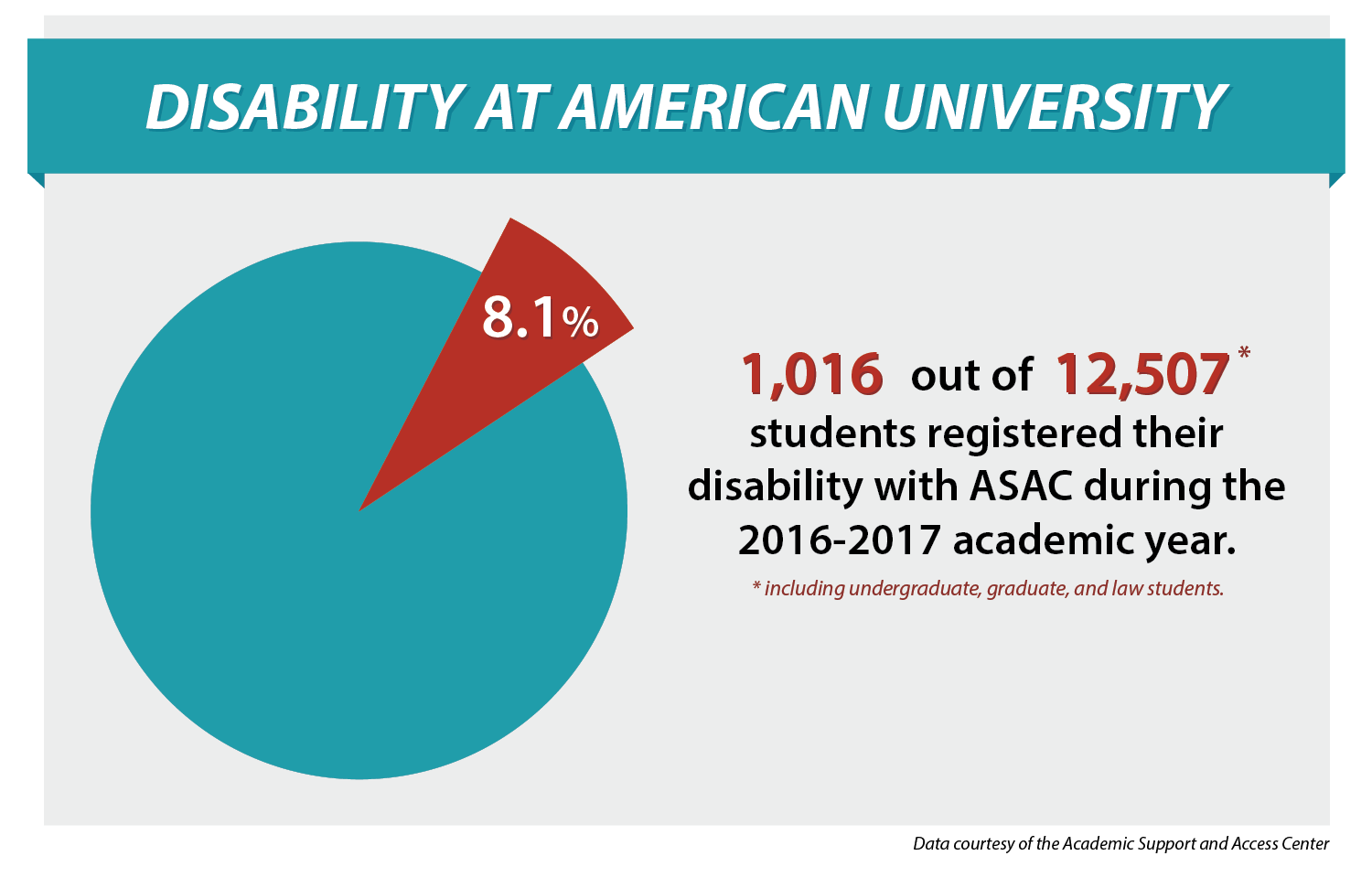

The Americans with Disabilities Act defines disability as “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” During the 2016-2017 academic year, 1,016 students registered a disability through the Academic Support and Access Center, said Erica Gillaspy, assistant director of disability support. Gillaspy said she could not specify the nature of those disabilities to protect those students’ privacy.

Students with physical disabilities fall under Gillaspy’s purview in addition to other types of disabilities, including learning and psychological disabilities.

Several students with physical disabilities told The Eagle that the University provides adequate accommodations within the classroom.

However, they feel overlooked outside of the classroom. They said communication about campus resources, their peers’ attitudes toward physical disability and inclusion by professors all need improvement.

"It's something that able-bodied students just aren't aware of," said Rebekah Ginsburg, a junior in the School of International Service who has joint pain. "It would never cross your mind if you don't have to take the elevator."

Academic Support and Access Center can only go so far

For students with physical disabilities, ASAC is the primary entry point for accommodations. Students can register there to disclose a disability. The office supports disabled students, anyone seeking academic assistance and student-athletes, Gillaspy said.

ASAC has a legal obligation to offer “reasonable” accommodations for all students that come to their office with documentation of their disability from a doctor, she said. Access looks different for every student, Gillaspy said. Ten full-time, two part-time and two graduate student staff make up the disability support department within ASAC.

Sometimes, a student’s request for accommodations cannot be met.

ASAC helps Ginsburg gain physical access to her classrooms because it is difficult for her to climb stairs. She said ASAC has been great about helping her schedule classes in buildings with elevators. However, this takes time and effort, which can be difficult for college students when planning their schedule, she said.

To ensure students are assigned to a classroom they can physically access, the registrar’s office groups students into cohorts based on type of accommodation needed, Gillaspy said. This helps the registrar assign classrooms based on each cohort’s specific needs.

“You are constantly thinking of every piece of the puzzle that needs to be considered,” Gillaspy said.

It becomes complicated when students require multiple accommodations or their accommodations can’t be completely met. Ginsburg experienced this last semester when she needed her science lab moved from Hurst Hall, which does not have an elevator. There were no other labs available.

“You just kind of have to suck it up,” Ginsburg said.

ASAC does their best to not reject a student’s request, Gillaspy said. If a student brings documentation to their office, ASAC provides them with accommodations.

“We are never just saying ‘no, bye,’ we are saying ‘no, but…’ or ‘no, not right now,’” Gillaspy said.

Zoey Jordan Salsbury, a senior in the School of Communication, has fibromyalgia, an unpredictable condition that causes unplanned muscle pain. This can make it difficult to request accommodations, like missing a class or getting an extended deadline, in a timely manner.

“It’s harder to get an excused absence in college than it is in high school," Salsbury said. "If you’re in high school, you’re a minor, your parents call and say ‘they’re sick.’” They trust your parents and you get an excused absence and everything’s fine.”

Salsbury said some students are hesitant to seek help from ASAC as they do not want a disability written in their records.

Some students also don’t want to interact with the student staff in the office, even though they don’t have access to student files, Salsbury said. Gillaspy said undergraduate students work at the desk doing administrative tasks, and some graduate students support staff on tasks like securing testing accommodations. All staff members are required to sign a confidentiality agreement.

Sometimes, Salsbury said, students’ busy lives prevent them from registering with ASAC or requesting accommodations. The accommodations available at the University may also be different than what a student received in high school, Gillaspy said.

“When you have like 20 things to do when you start the school year, a lot of times, disabilities can fall to the wayside," Salsbury said.

Accessibility needs extend beyond the classroom

Outside of needing accommodations inside the classroom, students find maneuvering around campus can also be difficult with a physical disability.

Michaelson drives to campus every day and uses handicap parking because she experiences chronic pain and fatigue on a daily basis. Aside from that, however, there are no additional parking accommodations on campus.

“They [campus planners] just didn’t think about it,” Michaelson said.

According to Section 504 of the ADA, "No otherwise qualified individual with a disability in the United States ... shall, solely by reason of her or his disability, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance."

This means that the University must provide accessible programs, not environments. For example, if a student has a class on the second floor of Hurst Hall, which does not have an elevator, the University can move the student’s class to a barrier-free classroom and maintain compliance with the ADA, Gillaspy said.

The University evaluates physical disability using the “functional impact” standard, Gillaspy said.

“We ask, ‘how does this have an impact on what it means to be a student at AU?’” Gillaspy said.

The University also aims to be proactive with accommodations, Gillaspy said. For example, East Campus was built to be fully accessible. However, the University also sometimes adds reactive accommodations, such as the lift outside the stairs to Hurst.

“As I’m growing in the field, I learn that not every student is going to be happy with what we provide,” Gillaspy said.

Opening a dialogue about disabilities on campus

Dr. Derrick Cogburn, director of the University’s Institute on Disability and Public Policy, created the world’s first barrier-free online graduate program in Disability Policy. The program is currently offered in Southeast Asia. The program’s courses are accessible for those with any kind of disability, whether physical, learning or otherwise, he said.

He said the same principles can be applied to all students, not just those at the graduate level.

For example, Cogburn said students have approached him about buildings they find physically inaccessible on campus, including Hurst Hall and the East Quad Building. He said the University must take advantage of technology, which can make accessibility more attainable.

Cogburn pointed out that even the newer buildings, such as the School of International Service, are not completely physically accessible.

“Accessibility is not just about, ‘do you have ramps and doors?’” Cogburn said. “There’s a lot more to think about in terms of universal design.”

Lily Coltoff, a sophomore in the School of Communication, recognizes the shortcomings of campus buildings, but she also said there is a lack of discussion about people with physical disabilities. Coltoff receives accommodations from ASAC. She would like to see more workshops about disabilities from the Center for Diversity and Inclusion and Student Government. CDI does offer a workshop on disability titled, “Exploring disAbility.”

“When the topic is brought up, everyone is like ‘let’s make Hurst accessible. Let’s make EQB accessible,'" Coltoff said. "No, we already comply by ADA standards. None of our buildings are going to change, so why don’t we focus on attaching no shame or no stigma to having academic accommodations or talk about invisible disabilities, which are a major concern.”

“None of our buildings are going to change, so why don’t we focus on attaching no shame or no stigma to having academic accommodations.”

- Lily Coltoff, SOC sophomore

Rachel Abraham, a freshman in the School of Public Affairs, has pulmonary hypertension, a rare condition that makes physical activity tough. This makes using stairs and walking long distances on campus difficult.

"I've had more people question why I'm taking lung breaks and I've had people tell me, 'No, I'm pretty sure you're just faking it because you're not blue and you're breathing normally,'" Abraham said.

Support from professors is needed, students say

Students with physical disabilities also look for inclusion from professors. Services provided through ASAC can only extend so far, and decisions are sometimes left to the instructor’s discretion.

“I have flexible attendance through ASAC, but some professors won’t accept that,” Michaelson said. “You can have accommodations as long as they don’t change the nature of the class. If attendance is the main component of the class and that’s what we’re graded on, there’s nothing you can do.”

It is important that students voice these concerns to their professors to make their learning space more accessible, Gillaspy said. ASAC looks to provide accommodations as best they can.

“I want them to feel they have the access they need to be successful here,” Gillaspy said.

It is crucial for students to disclose their disabilities as they see fit, she said. Her office can’t force anyone to register their disability, nor would they want to, she said. They also don’t do much outreach to students who are not registered with ASAC because disability is “such a personal issue,” Gillaspy said.

"My general life advice to anyone, if you're looking for accessibility or not, is take the first step..." Abraham said. "You still need to advocate for yourself if you want to get anything done."

bcrummy@theeagleonline.com and ntogrul@theeagleonline.com

Correction: This story initially incorrectly described Ariel Michaelson as being in a wheelchair. This was written in our print edition on Dec. 4, 2017. It has been corrected in both our edition, reprinted on Dec. 8, 2017 and online story to reflect that Michaelson is not in a wheelchair.