Standing in front of the sandstone doorway of a 12th century Khmer temple, your eye might be drawn to the myriad signs which evidence its antiquity: the two crumbling columns flanking its sides, the scalloping of the steps, worn away from years of feet scraping away at the stone, or the discoloration of the rock, blending from red to gray to brown to tan.

All these stimuli come together and convince your mind that what you’re looking at is old and therefore worth marveling at. It’s a fragment of the past, proof that the world is far older and larger than we can imagine.

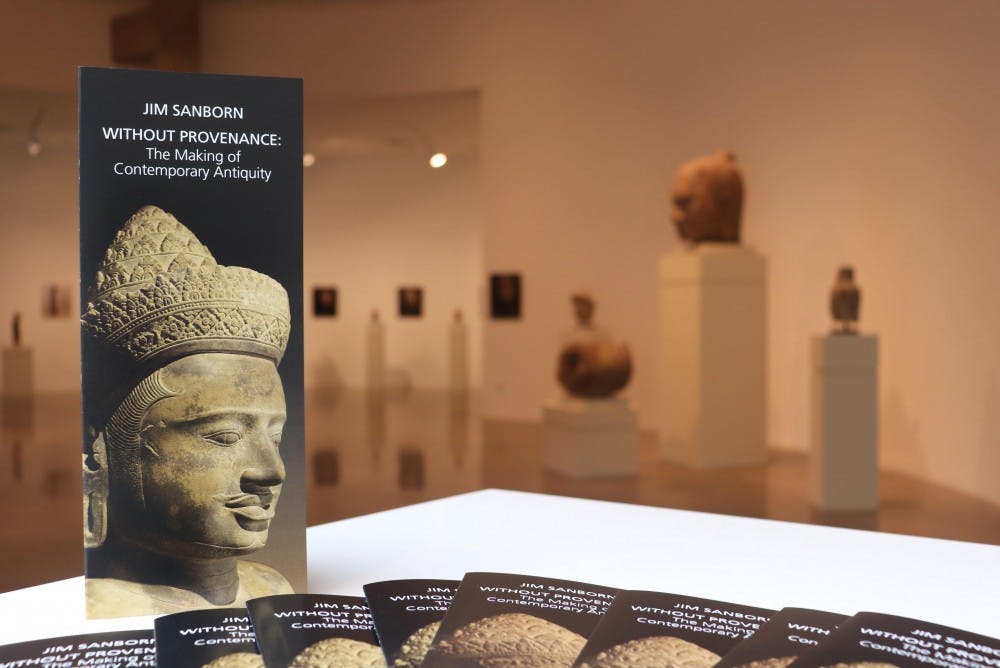

But at artist Jim Sanborn’s exhibit “Without Provenance: The Making of Contemporary Antiquity,” which is currently on display at the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, that sandstone doorway isn’t a fragment of the past. It’s a forgery that hasn’t existed for more than eight years.

“To tell you the truth, I wanted it to be extremely ambiguous,” Sanborn said.

The exhibition is a collection of Khmer sculptures made in Cambodia by professional sculptors and forgers which asks the audience to consider the purpose behind the collection of antiquities.

In Sanborn’s artist statement, he explains that an estimated 70 percent of Khmer antiquities in museums were either stolen from their original sites or forged. In creating this exhibition, he wants audiences to realize that the collecting of antiquities can harm countries’ cultural histories.

“My blunt opinion is: Why steal something when you can have something for zero risk, either financially or you know, legally, that’s just exactly like the original object, by buying a high-end reproduction or what I call a contemporary antiquity?” Sanborn said.

Sanborn traveled to Cambodia and met with sculptors to learn how they create fake antiquities, both in how they are carved and how they are chemically treated to appear aged.

The forgers were unwilling to teach Sanborn how to age the stone, so after shipping several commissioned sculptures to the United States, he spent more than a year experimenting with chemicals to recreate the timeworn surfaces.

“I had tables full of hundreds of tests of a whole variety of chemicals, every imaginable chemical and stain and botanical that you could think of to stain stone permanently,” Sanborn said.

At the exhibition, the fakes are arranged as they would be for an art auction. The work “A series of eleven foot bases” is held aloft by plain, black, utilitarian metal pedestals. Sanborn also designed a mock “presale catalog” which describes the works and the price they might go for at auction. Both the practical displays and the catalog communicate to the audience that the aesthetic appreciation of the work is secondary to its monetary value.

“There are various exposés and books written about the connection between looted antiquities and major auction houses in the United States and Europe,” Sanborn said. “I had to figure out a way to present my objects in a believable fashion and so I chose to do a faux auction catalog.”

The audience member becomes the art collector. At first glance, he or she may not know what is real and what is fake, what is worth appreciating and what is worth brushing aside because it isn’t a genuine antiquity. Once an audience member realizes that all the objects are fakes, are they no longer worth looking at? Do they no longer hold value?

While the audience puzzles over these difficult questions, the aesthetic beauty of these works remains.

“You’re terribly impressed with the quality of the fakes,” said Marie Kissick, who volunteers for the museum.

“A sandstone standing Shiva” is particularly impressive. The intricate patterning of its hair and the near-perfect symmetry of its face were still the product of a skilled sculptor, even if that sculptor wasn’t born in the 10th century, as the mock catalog claims.

Sanborn wants the audience to appreciate beauty for beauty’s sake, but he doesn’t think these sculptures need to be ancient to be beautiful.

“There is something very tangible about holding an ancient object in your hand,” he said. “That said, in today’s auction market … we now realize things are going extinct. Why kill an elephant? Why use a tiger for something other than its beauty in the jungle? Why loot a Khmer temple?”

Ultimately, audiences should be thinking about how an antiquity ended up in a museum. Sometimes, that might not be where it belongs.

“I hope that the 21st century will be the beginning of a more ethical kind of collecting,” Sanborn said, with museums and auction houses “hopefully collecting for beauty rather than stealing somebody’s culture or killing some animal.”

“Without Provenance: The Making of Contemporary Antiquity” will be on display at the American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center until Dec. 16.