Eliot Spitzer, the recently deposed Democratic governor of New York, will be forever remembered as the man who resigned from office amid a prostitution scandal. "Client 9" will go down as his moniker, and people will forget all about "Governor Steamroller," "Mr. Clean," the "Sheriff of Wall Street" and Time magazine's "Crusader of the Year." More importantly, people will forget about the legacy he built to earn those nicknames: a legacy of strong-arm tactics and an anti-business agenda.

During his time as attorney general and governor, Spitzer used blatantly underhanded and often highly personal tactics to dislodge from power those who displeased him. Fox Business notes that in order to take down Richard Grasso, then the head of the New York Stock Exchange and a respected figure on Wall Street, Spitzer threw the book at his target, attacking everything from the executive's high pay package to making implications of infidelity. Upon hearing news of Spitzer's liaison, Kenneth Langone, another former director of the NYSE who spent years fighting Spitzer on the Grasso matter, remarked to The New York Times, "He actually believes he's above the law. I have never had any doubt about his lack of character and integrity - and he's proven me correct." This tendency to drag his opponents' personal lives into the public eye has prompted some smirks from his victims, satisfied to see Spitzer's career die by the same sword.

Spitzer's tactics often didn't even involve a court date. He found himself able to force companies to endure the desired penalty simply by threatening a public lawsuit. Spitzer, Slate notes, "didn't simply indict. He issued press releases." Unwilling to risk a decline in stock prices, many companies found it easier to pay Spitzer's fines, regardless of whether they felt they would win the potential lawsuit. According to Slate, facing a battle against a powerful attorney and fighting the consumer distrust brought on by Spitzer's public statements, investment firm Merrill Lynch lost $5 billion in a matter of days, prompting a quick settlement.

Rudy Giuliani, the former New York City mayor, once joked that he felt like he needed a shower after being in a room with Spitzer. Little did he know how those words would ring true today. Still, in Giuliani's case, he simply referred to the distasteful tactics with which Spitzer approached his job, a sentiment shared by many on Wall Street. When the news of the governor's scandal broke, a veritable sigh of contentment arose from the stock exchange. "Today," noted the Wall Street Journal, "his enemies are hemorrhaging Schadenfreude." "His legacy as a Wall Street reformer may wither," offered U.S. News and World Report. And countless media outlets across the country have not been afraid to point out that, in a shocking bout of irony, Spitzer just this year increased penalties for a number of prostitution-related crimes.

"This is not a victimless crime," Rep. Peter King, R-N.Y., told the Times. "I've never known anyone who was more self-righteous and unforgiving than Eliot Spitzer." Unfortunately, King will likely be among the few who remember Spitzer for this. Given America's love of sex scandals, the incredible dollar amounts that Spitzer extorted from businesses will be overshadowed by the dollar amounts Spitzer spent on a few nights with one Ashley Dupré. The $1.4 billion taken from firms such as Merrill Lynch and Citigroup will be forgotten for the price of a call girl. His cunningly planned removal of AIG head Hank Greenberg will be replaced with memories of his clumsy attempt to cover his own tracks. Sadly, the man who should be remembered as a strong-armed bully will simply be remembered as a tabloid curiosity.

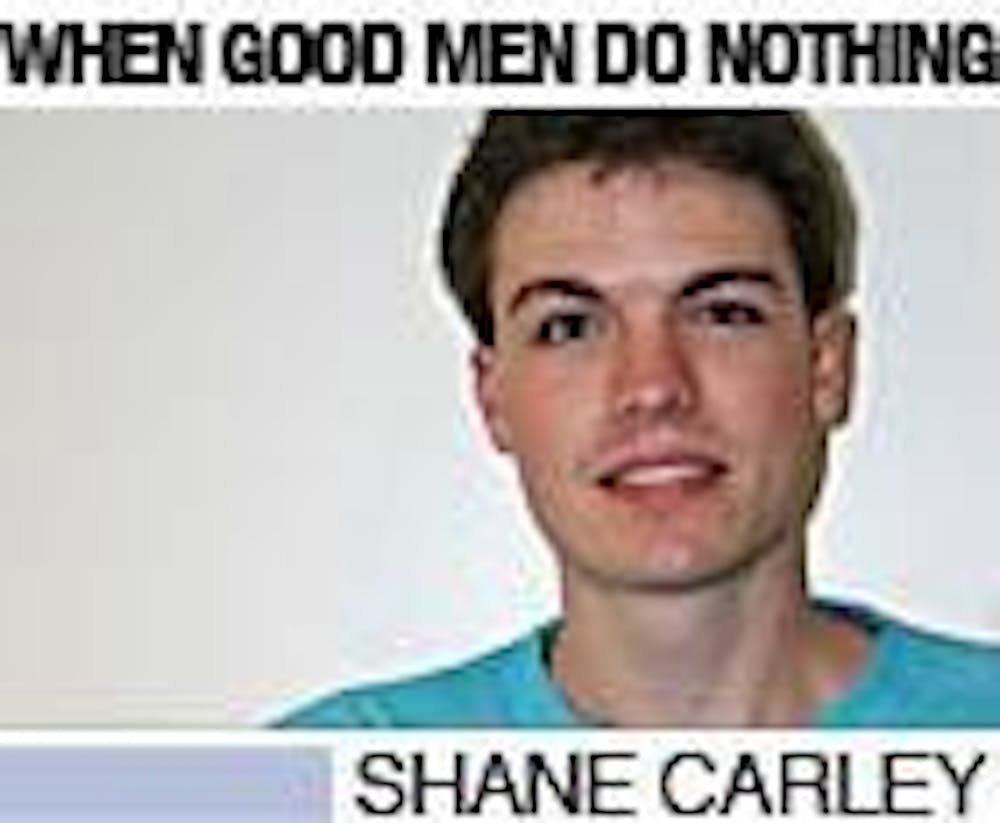

Shane Carley is a freshman in the School of International Service and a conservative columnist for The Eagle.