“Chasing Mavericks,” a surfing drama based on a true story, is a frustrating study in contrast. For the majority of its running time, this film is a gold mine of tired clichés: reluctant surrogate father-son relationship dynamics, awkward teen romance, melodramatic marital troubles and vapid “inspirational” dialogue.

In the last 15 minutes, however, the movie pulls off a suspenseful climactic sequence almost jarring in its effectiveness. A movie that only comes to life in its last fifteen minutes is hardly worth recommending, but “Chasing Mavericks,” directed by Curtis Hanson (“Too Big to Fail”) and Michael Apted (“The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader”), deserves credit for a few moments of inspiration amidst a sea of mind-numbing blandness.

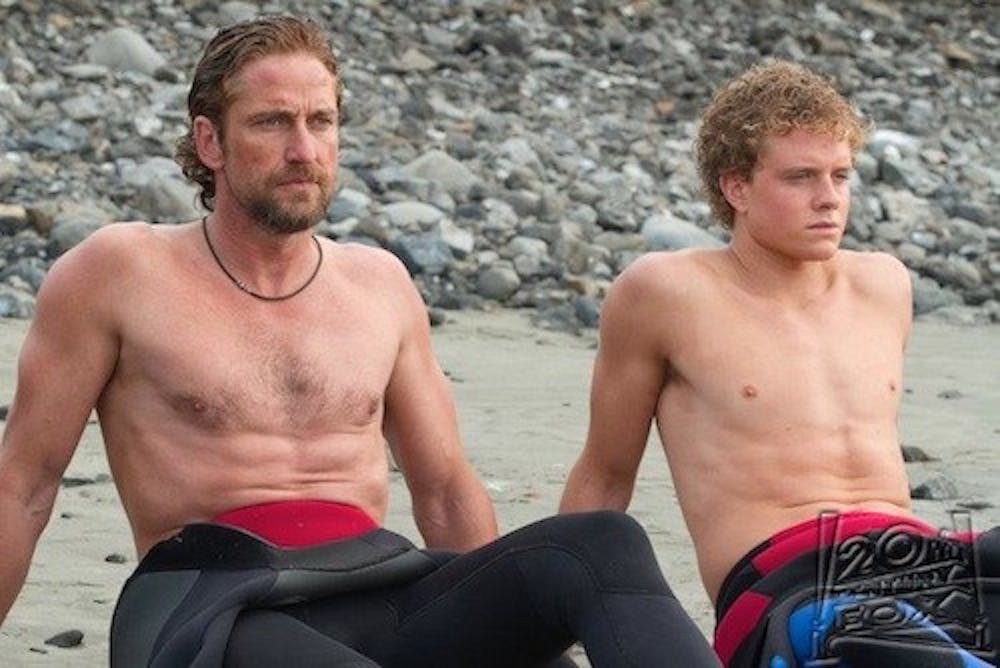

The film’s opening minutes establish the story quickly and without surprise. Newcomer Jonny Weston (handsome in the most basic, unsatisfying sense) plays Jay Moriarty, a daring teenage boy captivated by a series of uncommonly destructive waves called “mavericks,” located in Santa Cruz, Calif. Gerard Butler (“Machine Gun Preacher”) is uncomfortable and not particularly convincing as the scruffy surfer Frosty who saves young Jay from the waves and eventually becomes the teenager’s reluctant mentor. Jay experiences the expected difficulties as Frosty pushes him through a series of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual challenges.

Despite a refreshing lack of forced, manipulative drama, this movie’s stakes feel too low. Jay faces few enormous obstacles to achieving his goal of surfing mavericks: he’s physically fit, motivated and obedient, even when his eye strays to his childhood love Kim (Leven Rambin of “The Hunger Games,” who looks far too mature for boyish Jay). The movie doesn’t try to wring unnecessary histrionics from its simple premise: a boy wants to ride a wave, so he does.

On the other hand, the relative complacency of this premise requires screenwriter Kario Salem (“The Score”) to find other plot points for dramatic “interest,” including a disconcerting development involving Frosty’s wife and a pointless subplot featuring Jay’s childhood friend and a drug dealer. The filmmakers fail to find the power in the central relationship between Jay and Frosty.

“Chasing Mavericks” also raises the question of when clichés are acceptable. The best movies find the beautiful and unexpected within the clichés they employ, while the rest, like “Chasing Mavericks,” assume that the clichés alone justify the audience’s interest. They don’t. It’s no surprise that Jay sometimes fails to meet Frosty’s lofty standards, or that Frosty’s teaching replaces his active fatherhood, or that a group of utterly generic bullies serves as another arbitrary obstacle.

Furthermore, the actors and writing aren’t impressive enough to elevate the movie beyond its lazy reliance on convention. Weston’s impact is minimal, Butler fails to impress and the other characters aren’t developed enough for the performances to matter.

Luckily, the inherent cinematic quality of the ocean serves as visual compensation. Gorgeous shots of the majestic waves are the film’s forte. When no one is talking, as in the aforementioned climax, the ocean takes on a paradoxical destructive beauty far more compelling than any of the human characters. When the characters repeatedly articulate the film’s most obvious themes of perseverance and determination, though, “Chasing Mavericks” crash lands.

Perhaps the best metaphor for this movie arrives when Jay surfs his first wave as a young child. Rather than lingering on Jay to capture the potent mixture of panic and euphoria, an abrupt cut whirls the movie seven years in the future, robbing viewers of the emotional foundation for Jay’s later tests.

“Chasing Mavericks” as a whole works in similar fashion. All of the necessary elements are in place. What’s missing is everything in between.

mlieberman@theeagleonline.com