Invincibility and invisibility go hand in hand in the late August Wilson’s “King Hedley II," now showing on the Arena Stage. Set in 1980s Pittsburgh, race and the absence of privilege unfold at the Southwest Waterfront’s beautiful fine arts venue.

With only six characters on a stark concrete stage, Pittsburgh’s Hill District setting put each patron in the intimate position of a community onlooker. A wife, mother, street prophet, childhood friend, swindler and title character King Hedley II himself represent the community. Trying to make a life for themselves, the cast is gripped throughout the three-hour play by love, regret, death and blind ambition.

In King Hedley II’s (Bowman Wright) case, hustling is essential. From the beginning, Hedley sows seeds of trouble by partnering with his best friend Mister (KenYatta Rogers) in a scheme selling stolen refrigerators. In their minds, working outside of the White Man’s rules is the only option if they want to become agents of their own destinies. Though both feel oppressed by the white man, neither takes responsibility for their own actions. This is a running theme throughout “King Hedley II.” In a state of systemic oppression, with no end in sight, how is a black man supposed to find a way out?

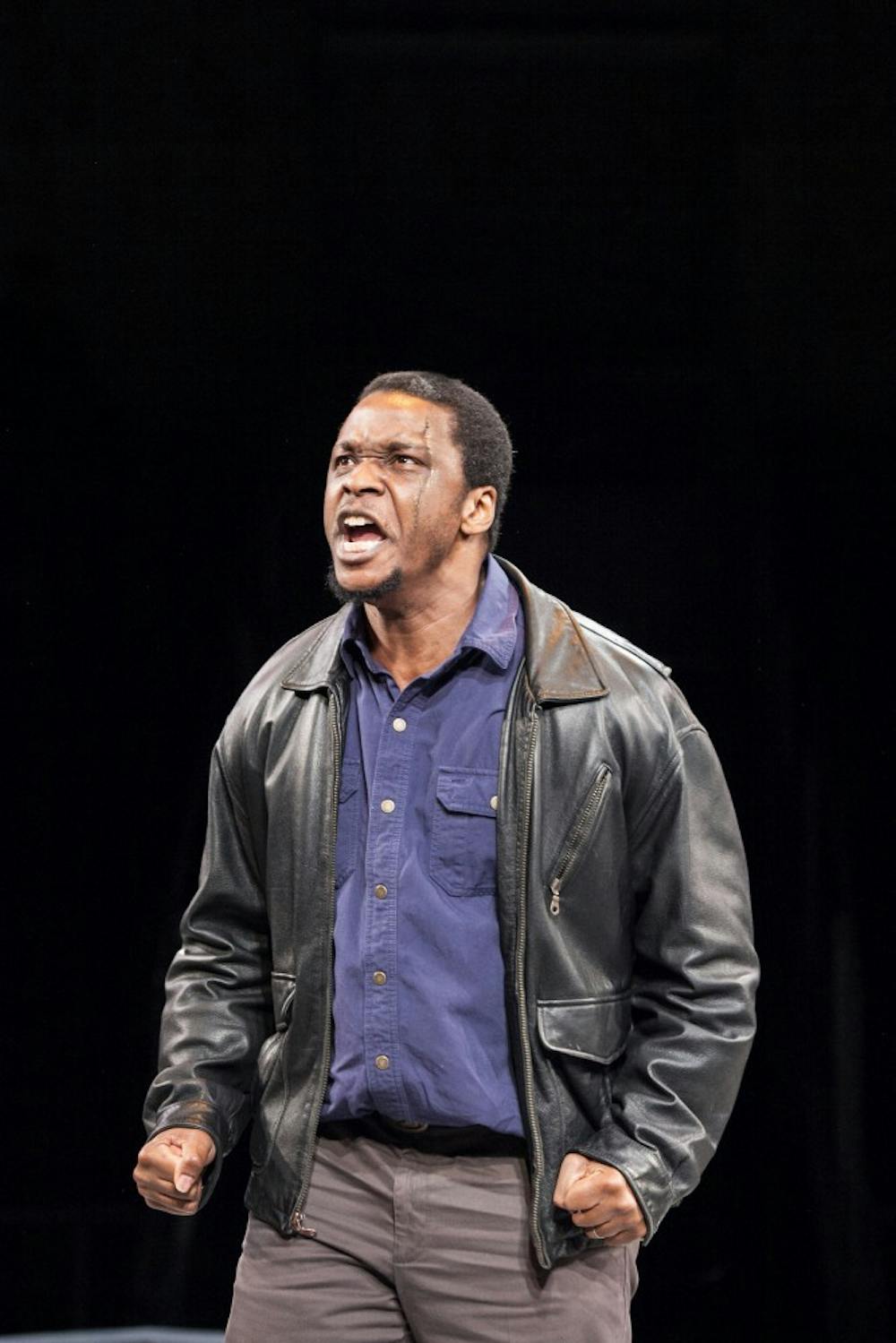

There are several key characters who offer advice to King Hedley II. One of the most brilliant performances is carried out by Stool Pigeon, played by the incomparable Andre De Shields. Hedley, in his often chaotically furious monologues, curses the world around him, which doesn’t consider him a worthy addition to society. A prophetic and wise older neighborhood man, Pigeon urges Hedley to realize his own worth and to look inside himself for the answers to life.

Hedley knows that he is worth more than the world but struggles to personify his ambitions. In one of the play’s titular scenes, Hedley attempts to grow flowers in the gray, broken concrete-filled dirt. In his rage, Hedley is determined to make something in his immovable and uncontrollable world grow. This theme continues when Hedley’s wife Tonya, played by Jessica Frances Dukes, reveals a pregnancy. Despite Hedley’s optimism and interpretation of the child as a second chance, Tonya’s realism frustrates Hedley. Citing a cycle of poor mothering skills that runs through her family and the people around her, Tonya makes a case against bringing another life into this burdensome world.

The play’s strength came from the chances characters could use monologues to set themselves apart. Frances Dukes’ fiery and frustrated timeline of becoming a teen mother and seeing her daughter do the same did more for her character than interactions with Hedley ever could. Comic relief wasn’t too far from the stage. Much like real-life hardship, the comedic errors and asides gave a bit of reprieve for the three-hour-long performance.

Running on the Arena Stage until March 8, “King Hedley II” looks into a microcosm of black lives in the 1980s. Living in what is sometimes misnamed as a post-racial society, being provided a look into the--though dramatized--history of minority struggle helps give perspective to current race relations in post-racial America.

Greater yet, the focus on a black man’s evident self-worth and contrasting worthlessness to his community is still an issue in the wake of Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown’s untimely and politicized deaths. In King Hedley II’s case, the battle isn’t so much between himself and society as a whole. The battle is between his impulsivity and his conscience.

@Psjmarie - jsmith@theeagleonline.com