This article originally appeared in The Eagle’s December 9 special edition.

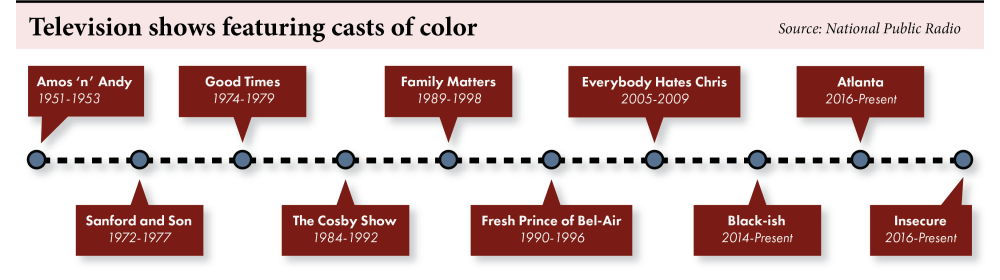

Hollywood still has a lot to learn. The first all-black cast on a television sitcom debuted on “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” back in 1951, but the show was widely regarded as racist. In the years following, there were few uniquely African-American voices in the medium until now. This fall, shows like HBO’s “Insecure” and FX’s “Atlanta” have succeeded in conveying a side of the black experience that has often struggled to find a mainstream audience.

“There’s been a lot of questioning about whether a black show could be broadly attractive and draw large crowds," Rachel Watkins, a professor in AU’s Department of Anthropology who studies racism in America, said. “Strides have been made in using the experience of black folk and black voices to speak to a more general audience.”

Enter actor and writer Donald Glover. A disrupter. A game changer. And now the creator and star of “Atlanta.” The show premiered this fall and reached an impressive one million viewers per episode. With “Atlanta,” Glover isn’t playing with or conveying any sense of racial tokenism. He plays Earnest, a guy from Atlanta who is about as typical as any 30-year-old.

“They [black movies and television in 2016] all show different aspects of ‘black life’ that suggest that strides have been made,” Watkins said.

Elisha Brown, a senior in the School of Communication and co-president of the AU chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists, has always been an avid consumer of media. She is also an editor of The Blackprint, a student-run online publication that created a “safe space for people of color at AU to discover what’s going on in their communities, and their culture,” according to the publication’s website.

“[There is a] fear of ‘Atlanta’ being tokenized as ‘the black show for black males.’ Shows like ‘New Girl’ are called mainstream television,” Brown said. “Life for white people is codified as mainstream.”

Despite anxieties like Brown’s, this year has seen more film and television shows that depict black life but aren’t necessarily categorized as “black shows.” Cable series like “Atlanta” and “Insecure” and the critically acclaimed independent film “Moonlight,” which premiered in October, are projects with predominantly African-American writers, actors and creators that tell stories about everyday life without focusing exclusively on race.

“Donald Glover’s character reaches into stereotypes of him because he was marginalized as the black nerd and now he is able to debunk misconceptions and show people a different side of him,” Brown said.

Black life on screen

Mainstream films and TV shows are organized by two things: genre and race. The hope with shows like “Atlanta” and “Insecure,” which focuses on a black woman coping with her own flaws and dealing with the world around her, is that eventually they will not be seen as “the show about the black experience.”

“There’s a way in which their [children’s] consciousness is shaped by that [black life on screen],” Watkins said. “There is beginning to be a saturation of black people in film and TV.”

The breakout of these shows this fall brings a relatable experience to life, something which reminded Brown of the show “Good Times,” which ran on CBS from 1974-1979, and which she and her family watched episodes of when she was young.

“Good Times” told the story of a black family in a housing project in Chicago. The characters always struggled to find or keep work, but at the end of the day they found solace in each other. “Atlanta” similarly articulates the nuances of lower-middle-class life in the city, rather than relying more heavily on themes of race.

“Happiness [on ‘Good Times’], even through bad times, was more relatable than whatever was going on in ‘The Cosby Show,’” Brown said, looking back at how she and many viewers perceived the two shows.

Unlike “The Cosby Show,” which aired from 1984-1992 and displayed an affluent, heteronormative, nuclear family that was not the norm in much of black America, Brown said she felt “Good Times” had an unshakeable authenticity.

“I’m not saying there were not core values displayed on ‘The Cosby Show’ that my family couldn't identify with. But the ability to talk about money, or the lack of it, on ‘Good Times’ was refreshing,” Brown said.

A shift in Hollywood

While the first all-black writing staff of “Atlanta” may seem to be a big leap forward, the coverage the series has received is eerily similar to the coverage “The Cosby Show” received decades ago.

In a 1992 review of “The Cosby Show,” New York Times critic John O’Connor said the show tackled “still another persistent network taboo” with a “cast consisting almost entirely of black performers who were not called upon to be silly clowns, pathetic addicts or menacing thugs.” Skipping ahead 24 years, the paper wrote in a similar vein when they called “Atlanta” groundbreaking, saying that it “is above all a layer cake of African-American life, bourgeois and street, hipster and old school.”

The similarities between how high-culture treated “groundbreaking” shows that featured black casts 30 years ago and now suggests just how little progress has been made. However, the sheer amount of media produced by black people today is able to get across the message that there are so many shades to black life that a single show can only speak to its specific group of characters.

“‘Atlanta’ signals a moment and we are in the process of analyzing it and asking what does it mean. As an anthropologist I think about the specific moment and what it signifies, but I also think longitudinally about how we talk and and signify these moments,” Watkins said. “If you go back and read some of the early reviews or some of the academic work or commentaries on ‘The Cosby Show,’ you would think you are talking about ‘Atlanta.’”

Such changes like the ones seen this fall have been driven by different artists who work to break down barriers in the entertainment industry. Donald Glover, Ava DuVernay, the director of the 2014 film “Selma” and the TV show “Queen Sugar,” and comedian Dave Chappelle are figures in Hollywood that have had a monumental impact on the industry while marching to the beat of their own drums.

By working outside of the mainstream, all three have found ways to infiltrate an industry that has long been dominated by white males.

“It’s very important for there to be a space to view and celebrate black cultural production, including in the form of television writing and having television shows and films, because that lends to viewing people as being human,” Watkins said.

Chappelle, like many of his contemporaries, struggled to overcome creative differences with executives who often failed to promote nuanced perspectives on black America. At the peak of his popularity in 2006, Chappelle abruptly left “Chappelle's Show” due to those differences.

“When he was on TV, he was a unicorn with the critiques that he was doing, and I think that given the time [Chappelle’s] show was on, it makes perfect sense that he walked away,” Watkins said. “He was able to recognize that ‘You know what, I see these people aren’t laughing with me they’re laughing at me, they’re not there yet.’ So good for him for not subjecting himself to that.”

Cultural shift

Since the Civil Rights Movement, there have been major instances of social activism that have reverberated in popular culture.

“Without [social movements], [black stories on screen] wouldn’t happen at all, but it speaks to the struggle that we are still regarding the value of black lives and black voices,” Watkins said. “There should be an exponentially larger response on the part of Hollywood to this stuff.”

One example of a major historical moment that left an impact in the entertainment industry was the election of President Barack Obama, according to Gil Robertson IV, a journalist, author, and president of the African American Film Critics Association.

“Obama has had an immeasurable impact on opportunities in a lot of different areas of life,” Robertson said.

He also attributes the symbolic importance of shows like “Atlanta” and “Insecure” to changes over time. Having the first African-American president is a hugely significant moment that reminded people everywhere that any dream is attainable with hard work, Robertson said.

“Natural progression, we have our first black president, even on a subliminal level, unconsciously that’s changed how people view the world, how they see themselves and how they see others,” Robertson said.

Hollywood figures like Glover and Cheo Hodari Coke, who directed the first black superhero show “Luke Cage,” are producing content in a variety of ways on a variety of platforms, Watkins said.

“I love the idea that for us to be present and for us to be heard it doesn’t require film in the traditional sense anymore,” Watkins said.

The sheer amount of time that it has taken for non-stereotypical roles to be available in cinema speaks to not only the societal changes that have taken place, but to the struggles that it takes to get out an authentic voice, Richardson said.

“There are a lot of examples out there of people who have rocked to their own beat…but it can be a lonely ride,” Richardson said.