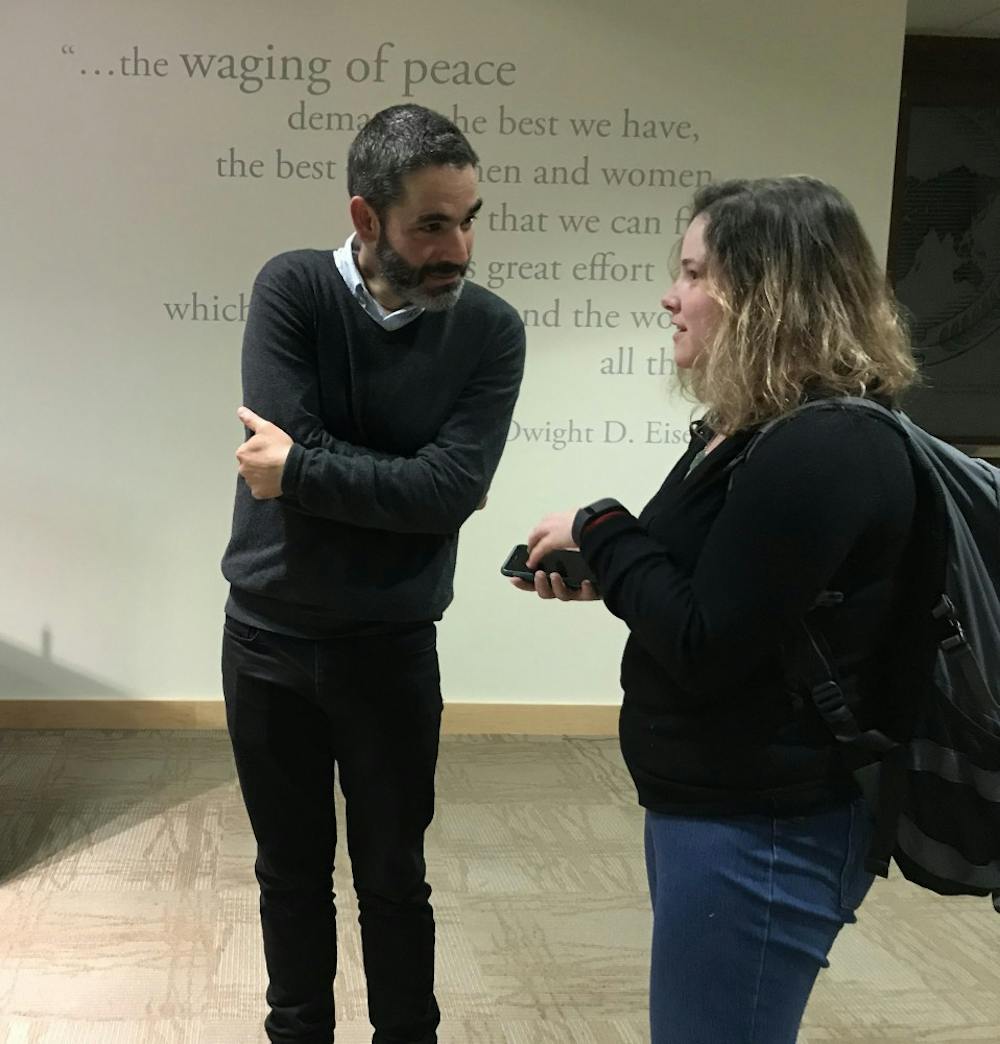

Mexican director Fernando Eimbcke headlined a panel discussion on Oct. 25 on his approach to filmmaking. He also gave advice to student filmmakers in the audience.

Professor Jeffrey Middents led the discussion, and professors Núria Vilanova and Dolores Tierney appeared on the panel with Eimbcke. Middents said the event was five years in the making.

“I will confess that when they asked who we wanted to bring, five years ago you were the name I put on the list,” Middents said. “I have been waiting five years for this.”

During the event, Eimbcke spoke about his style of filmmaking, stating that it derived from his actors. On the set of his film, “Temporada de patos,” Eimbcke’s seriousness frustrated young actor Diego Cataño. When Eimbcke instructed Cataño not to play on set, other actors inspired Eimbcke to embrace play.

“He said, ‘But if we can’t play, isn’t that very boring?’” Eimbcke said. “That night I realized, yes, the movie is about playing, and playing is about risks, and so we take those risks.”

Since “Temporada de patos” was released in 2004, Eimbcke has gone on to direct two more films: “Lake Tahoe” in 2008 and “Club Sandwich” in 2013. Eimbcke was in D.C. to promote a screening of “Club Sandwich” at the Inter-American Development Bank, a rare stateside screening for a film not released in the U.S.

Eimbcke said his influences come from around the world, ranging from American independent director Jim Jarmusch to Italian neo-realist Vittorio de Sica to famed Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu.

“It’s like a dialogue between cinemas all around the world,” Eimbcke said.

Eimbcke is now working simultaneously on two documentaries and a TV series. When working in television, Eimbcke said he has been frustrated by the pressure to focus heavily on the show’s plot.

“I think plot is like a snack, and we should be more aware of it,” Eimbcke said. “It’s like a snack you keep eating but you never have the full experience of a full meal.”

The possibilities of documentary, on the other hand, excite Eimbcke. He cites the rise of female directors in Mexican documentaries as a welcomed development in the field.

“The film industry is very machista,” Eimbcke said, referencing the Spanish term for male-dominated and chauvinistic. “There is something really important happening in documentary.”

Mexican cinema has experienced a new wave in the past two decades. Beginning roughly in 2000 with Alejandro González Iñárritu’s acclaimed “Amores Perros,” the wave brought directors Iñárritu, Alfonso Cuarón and Guillermo del Toro international success. The three directors have accrued 17 Oscar nominations and six wins collectively.

Today, Eimbcke sees a bustling film industry in his native country that he feels frequently plays it too safe. He feels passionately that there is a lot of original work being produced in Mexico that lacks proper distribution channels.

“If you want to create a movement, it’s not just about producing films, it’s about creating audiences,” Eimbcke said.

Eimbcke said the lack of multiple film distributors in Mexico has stifled more original work and created “commercial films.” With his work, Eimbcke has been praised for his ability to depict daily life in Mexico and Mexico City, but his originality has sometimes run at odds with the commercial sensibilities of major funders, he said.

“It’s amazing what’s happening in Mexican cinema because we have a lot of films in film festivals all around the world,” Eimbcke said. “The three Mexican filmmakers have done great in the United States, but those weren’t Mexican films.”

During the panel discussion, Eimbcke talked about all aspects of his work, from costuming to editing to his use of music. Eimbcke’s biggest piece of advice to the students present was to throw out the rulebook.

“In film school they tried to teach me there were formulas, and there’s no formula,” Eimbcke said. “You should take risks, that is how art is done.”