Global community has become more than just combining our technology, cultures and travel. As the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s (NMNH) newest exhibit, “Outbreak,” shows, even our viruses are becoming global phenomena. Rather than focusing on the technicalities of these diseases, the exhibit is able to personalize each phenomenon to the viewer as well as cultivate a conversation around general health practices.

According to the museum, the modest 4,250-square-foot exhibition “invites visitors to join epidemiologists, veterinarians, public health workers and citizens of all ages and origins as they rush to identify and contain infectious disease outbreaks.”

Filled with case studies and interactive games, the exhibition, which opened May 18, seeks to define and expose individuals to issues such as pandemic risk, emerging threats and global health security.

The entrance to the exhibit begins with the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic to highlight the social and emotional fallout of outbreaks. By drawing attention to the 100-year anniversary of the flu pandemic, “Outbreak” also raises public awareness about other widespread public health risks.

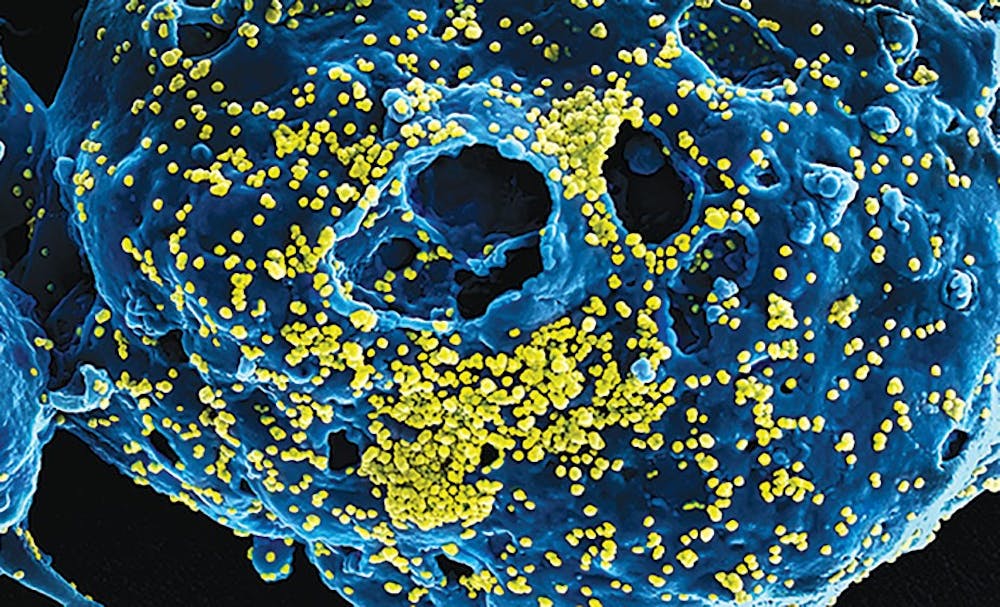

The highlighted infectious disease physician, Dr. Daniel Lucey, travels to the front lines of outbreaks and proposes his idea for an exhibit about “zoonoses” -- diseases caused by pathogens that are transmitted to humans by domestic animals and wildlife, such as the Ebola virus, the Zika virus, HIV and influenza.

The exhibit breaks down how various human activities increase opportunities for these zoonotic infections to spread with the help of human behaviors. Examples include urbanization, industrialized food production, global travel oranimal trade with touching wild animals, traveling when sick, non-vaccination or unprotected sex. Broadening the context of these diseases allows for the message of “Outbreak” to transcend past the limitations of the exhibit. Rather, it is about human, animal and environmental health connected as “One Health.”

Since 1981, Lucey has authored or co-authored nearly 90 medical papers and 17 book chapters. He believes that “zoonoses with a wildlife origin are a significant threat to global health, but many people are uninformed about how and why outbreaks of these diseases are becoming more frequent.”

However, the exhibit expands beyond the origins of zoonotic infections and humans’ role in spreading animal-borne diseases to address how outbreaks have been handled throughout history.

For example, according to the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), “more than 70 million people have been infected with the HIV virus and about 35 million people have died of HIV” since the outbreak of the epidemic. And a little over four years ago, the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa became the largest in history. This outbreak took the U.S.by surprise and caused widespread fear even though the Centers for Disease Control and Protection (CDC) reports only “eleven people were treated for Ebola in the United States during the 2014-2016 epidemic.” Yet these viruses aren’t new and neither are the socio-cultural implications on the communities they affect.

But Sabrina Sholts, curator in the Department of Anthropology at NMNH, says, “What had changed was the ecological context: an increasingly connected and human-dominated world. Following its ‘spillover’ from a wild animal in rural Guinea, the virus spread along road networks from villages that were no longer isolated.”

Following the paths of the crowds, visitors can play an interactive game to explore the consequences of these diseases virtually around every corner. The single player game in the section about Zika drew me in once the middle schooler in front of me ran away rather disgruntled at not being able to figure it out.

The game sets the player up as a doctor with limited files and information on various patients and their symptoms. By narrowing down certain pathogens to certain symptoms, the player is then able to diagnosis the patients with the appropriate disease and medication.

This simple single player game allows visitors to understand how diagnosing diseases such as these, especially during times of outbreak, can be an extremely difficult task. Yet the exhibit does not end on such a pessimistic note. Rather, it shows how various organizations and fields can work together towards raising awareness and proposing solutions.

As it highlights figures like author Olga Jonas, epidemiologist Larry Madoff and journalist Lawrence K. Altman, “Outbreak” is a step forward in turning the public’s attention toward the danger of infectious diseases and the potential for collaborative results.