She never thought this would be the way she started her freshman year. After a night of drinking in her residence hall, Rachel was transported to a local hospital after a resident assistant believed her health was at risk.

After that night, Rachel was on the hook for a $400 ambulance bill and faced a mandatory meeting with the Health Promotion and Advocacy Center (HPAC). But the worst part, she said, was having to talk to her parents the next day.

“I felt so bad that they worked so hard for me to go here and this is one of the first big things that happened,” Rachel said. “I had to tell them about me being transported before I could tell them about, like, a good test.”

Rachel is far from alone. She is one of several students who spoke to The Eagle about their transport to local hospitals. All of the students requested anonymity and their names have been changed.

After a significant rise in alcohol-related transports involving AU students, the University is grappling with how to promote safer drinking habits within what students and administrators say is AU’s and Washington’s “work hard, play hard” drinking culture.

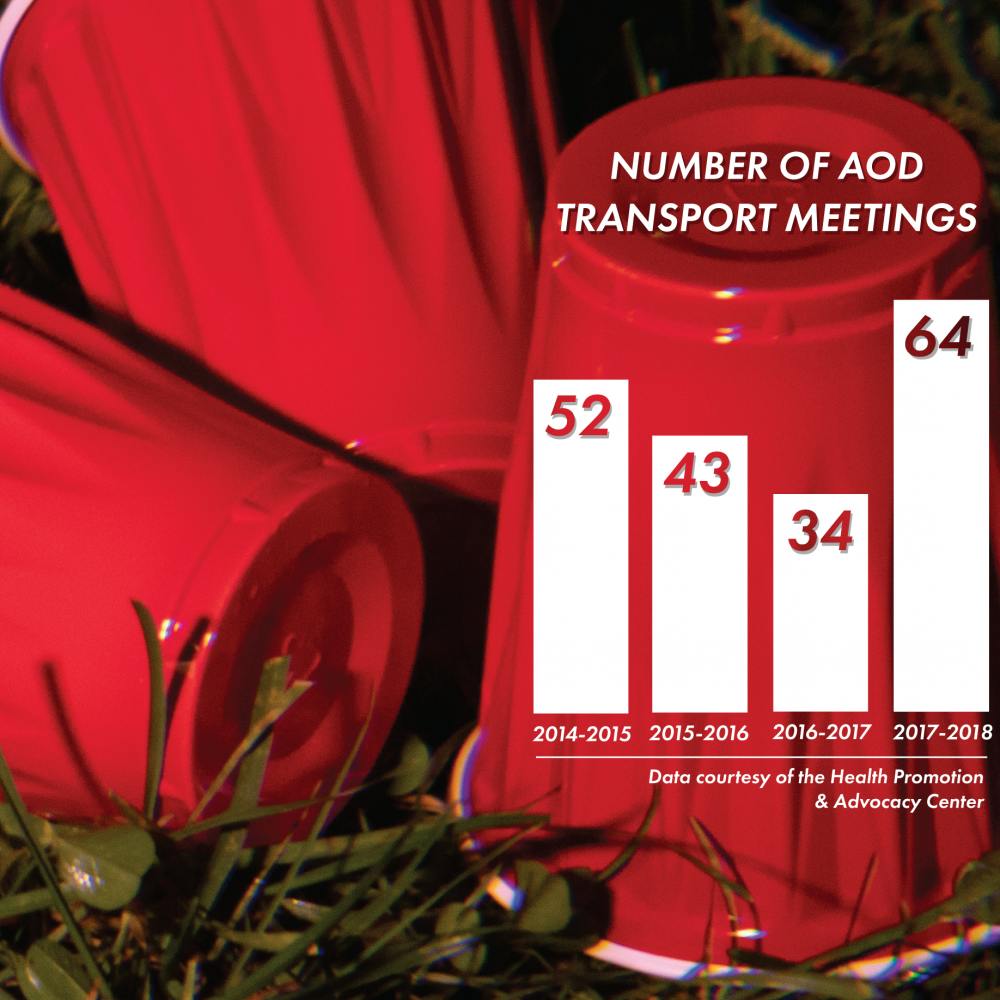

In the 2017-2018 academic year, the total number of alcohol and other drug-related transports almost doubled as compared to 2016-2017, rising from 34 to 64, according to data from Pritma “Mickey” Irizarry, the director of HPAC.

Students like Rachel say alcohol abuse has been normalized at the University, creating a “subculture” of students who don’t take binge drinking seriously.

“It’s become such a joke, which for me is super painful to see,” Rachel said. “The binge drinking is the saddest thing that I’ve seen at AU and that absolutely is at the core of … how frequently [transports] happen.”

How AU’s transport process works

An alcohol and other drug-related (AOD) transport occurs when a student is found to be so intoxicated that an AU residence life staff member or AUPD think it’s necessary for the student to be transported via ambulance to the hospital, according to Lisa Freeman, AU’s director of residence life and residential life education.

If a student is transported for the first time, AU takes a “wellness” approach and does not document the incident as a conduct violation, according to administrators. Instead, the student must have an educational meeting with HPAC and, on some occasions, meet with the Dean of Students office for a follow-up investigation.

“The most important thing is care and concern,” Freeman said. ”We want students to get the help that they need and not be worried about getting in trouble and more about being safe.”

Michelle Espinosa, the associate dean of students, said that the procedure for dealing with students who had an AOD transport is almost the same with or without the conduct violation. But, she said, students are more open-minded when they know there will not be a conduct violation going on their record.

“A student who’s concerned about a conduct record is not going to be open to discussing and learning what they can do differently next time because they’re going to be so worried and mad about the conduct record,” Espinosa said.

Following the increase of transports last year, Irizarry created a new role within HPAC, titled the “coordinator for alcohol and other drug initiatives,” that was filled by Yoo-Jin Kang at the beginning of the fall semester.

Previously, transport-related meetings were handled by a staff member with several other duties. Irizarry felt that it was necessary to have a member of HPAC’s team who specifically focused on educating students on alcohol and drug issues on campus.

“We know the statistics at AU when it comes to alcohol and drug use,” Irizarry said. “We know that there’s a need for education, awareness, intervention and strategic planning.”

Kang said one of her roles is to meet with students after their transports in a non-disciplinary setting. She discusses the events leading up to the transport to make sure there are no other underlying issues that the student is dealing with and also asks how they are coping after the incident.

“We don’t want to put Band-Aids on it,” Kang said. “The reality of alcohol misuse is that it’s never just about the alcohol.”

Students weigh in on “normalizing” of transports at AU

Several students, whose names have been changed to protect their identity, described harrowing experiences during and after their transport experience. Many cited the high financial cost of calling an ambulance to take them to the hospital, which can cost anywhere from $300 to $1,000 depending on insurance, according to the D.C. Fire and EMS Department. Ryan, a sophomore who was transported last year, said that the bill cost his family $900 and he struggled to pay it off.

Emily was a freshman at AU last year, but after a near-death experience and AOD transport from a club, her parents eventually pulled her out of school. She said that the space from alcohol has helped her to stay sober and realize she had become reliant on substance abuse.

After taking shots at a D.C. club, Emily became unresponsive and foaming at the mouth outside on a sidewalk, she said. A fellow AU student, who she does not know, took care of her and called an ambulance. When the ambulance arrived, Emily had to be resuscitated and had an emergency stomach pump at the hospital.

“At the time, I thought I was invincible, like nothing can hurt me, nothing can stop me, I’m going to be fine,” Emily said. “But after I was in a hospital and woke up with things in my arm [and] people around me concerned, I realized I’m not invincible. I’m human and you should treat your body the best you can.”

Maya Krieger-DeWitt, a sophomore, became responsible for someone who lived on her floor who she only vaguely knew when she walked into a party. She saw the girl being carried out and said she had to stay up very late taking care of the girl and answering questions that she knew little information about.

“I would never want to be in a situation where a stranger had to be responsible for me being alive, so I never pushed it remotely to that point,” Krieger-DeWitt said. “[Being transported] is not a solution, like ‘I’m going to drink so much because I’ll just be transported.’”

Several students interviewed by The Eagle said that transports became normalized to the point of becoming jokes. Their classmates often referred to an ambulance as the “wonk bus” in reference to the AU shuttles that take students to and from the Tenleytown Metro.

“A friend was like ‘my ride is here’ or ‘try to get transported tonight,’” Rachel said. “I kind of laugh along if it’s friends that I don’t know that well, but that’s not OK.”

Harry Solomon, a former resident assistant who graduated last May, said any transports by ambulance on AU’s campus are immediately assumed to be alcohol-related.

“What I found kind of upsetting is that the sight of the ambulance on campus, especially on the south side of campus, automatically triggered people to think it's for alcohol because no matter what time of day, the assumption is it's for alcohol.” Solomon said.

Emily also found the way AU students described transports to be concerning.

“The way that the AU community felt about transports very much normalized it to me, but after talking to friends outside of AU and my parents, I realized how uncommon and dangerous getting to that point actually is,” she said.

Dissecting AU and the District’s alcohol culture

Irizarry and Kang, the HPAC staff members, said there are several factors that play into the use of alcohol and drugs at AU. The University lacks several elements that play into college drinking culture, including large athletic programs and Greek life housing on campus, Irizarry said. AU also does not have a high male-to-female ratio, which often is associated with higher alcohol consumption, Irizarry said.

However, according to Irizarry, factors that may increase the use of alcohol and drugs on campus are the University’s proximity to an urban environment and the presence of Greek life. Washington in particular has a reputation of binge drinking, with the highest rate of binge drinkers in the country. According to a 2017 study by the American Addiction Centers, 25.5 percent of D.C. adults say they’ve participated in binge drinking.

Irizarry said there’s a normalization of drinking in the young professional culture of the District. There's an image of young professionals that a lot of AU students aspire to be, Irizarry said: attractive, successful and well traveled. Alcohol is a big component of that, she said.

Since starting at AU, Kang has noticed the University’s “work hard, play hard” culture that is very much influenced by metropolitan D.C. culture.

“D.C. super encourages that -- happy hours after work, young professional happy hours and a lot of companies have free beer and wine in the office if you’re going to internships,” Kang said. “It’s just part of the metropolitan lifestyle.”

The stress students face at AU is also part of the equation, Kang said.

“It’s about getting ‘effed up,’ but it’s also about working hard, and that sort of makes up for it,” Kang said when describing students’ attitudes about partying culture. “When you’re super stressed, you don’t think as clearly and so the types of coping mechanisms you might go to, you might not think about very holistically.”

Kang said that white males are statistically the largest demographic of binge drinkers in the country. While there are more women than men at AU, it is a predominantly white university. This, as well as the way that the “American college experience” is portrayed in the media, can make it feel like high-risk drinking is what everyone does.

“‘Oh, everyone throws up or blacks out when they drink.’ That’s not true, but it may feel like that’s what normal behavior is,” Kang said.

Sophia, a sophomore who was transported at another university during her freshman year, said her transport experience was caused by exactly that mindset.

“My mistake was thinking that having a normal college experience was blacking out and taking things to a level I normally wouldn’t have,” she said.

Students are often surprised to hear statistics that the amount of drugs and alcohol students actually consume is considerably lower than what they think it is, Kang said.

“Seeing an ambulance is a really loud visual and then people might then assume, ‘Oh that's normal,’ but in reality that might be the exception,” Kang said.

Kang said that in the future, she and HPAC are working to address the underlying issues behind binge drinking and drug use, rather than seeing the issue as a “party problem.”

“Alcohol use on our campus is including or excluding certain people and setting a certain cultural norm that that maybe we don't want to have,” Kang said.