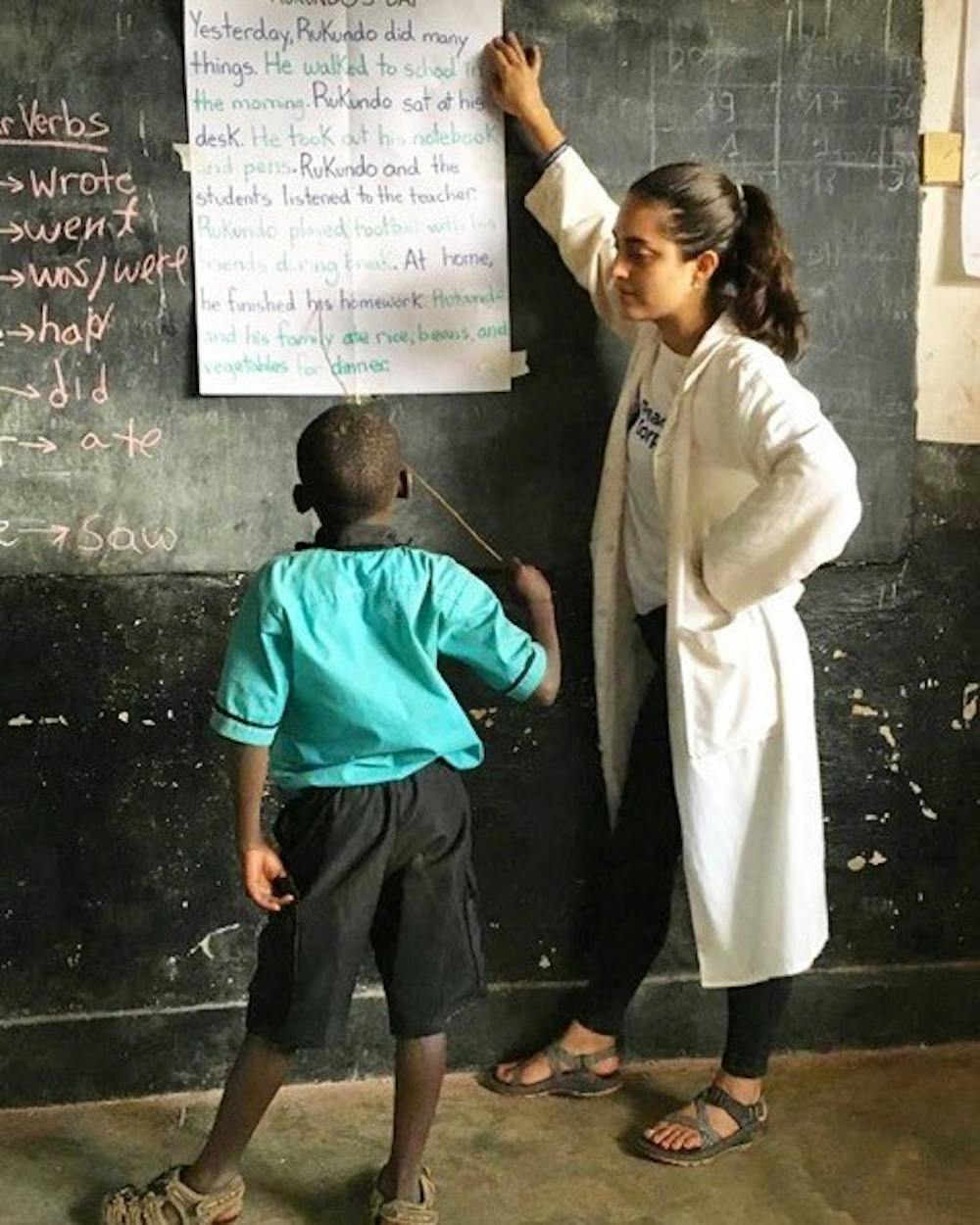

For Ana Santos, the time finally felt right to join the Peace Corps. After graduating from AU in 2014 and working professionally for four years, Santos left for Rwanda to become a Peace Corps volunteer in September 2018.

But like more than 7,000 other Peace Corps volunteers who were evacuated from their host countries because of the coronavirus, Santos is now back in the United States. She had about eight months left in Rwanda before she was evacuated.

“I finally figured out what was the best way for me to serve my community [in Rwanda],” Santos said.

With only a few days to pack up her things and return to the United States, Santos was unable to say goodbye to many of the people she had spent the past 18 months working and building relationships with.

“The whole process was really painful because I didn't get the kind of closure that I wanted. Everything felt so interrupted,” Santos said. “I had some time to say goodbye, but you know, it's never going to be enough.”

Santos isn’t the only AU graduate facing this circumstance. Charlie Castillo, who graduated from AU in 2019, was serving in Namibia.

“We had just gotten into the groove of ‘oh, this is our life for the next 24 months or so,’ and then all of the sudden we have to leave. It was a lot of painful goodbyes and soul searching after that,” Castillo said.

JennyLou Spoon, who also graduated in 2019, was evacuated from her Peace Corps post in Indonesia. She had been teaching English on the island of Java. Like Castillo, she began her service in September and still had 21 months left until she was set to return to the United States.

Spoon and her fellow volunteers were initially told in March that they would not be evacuated. A few days later, they were put on standfast, meaning they could not leave their site. Three days later, they were told to get to their consolidation point in Surabaya, Indonesia by midnight the following day, which was a nine-hour train ride away, on the other side of the island.

“It was pretty quick once it started to go,” Spoon said. “And a lot of people freaked out because they hadn't even started packing or anything.”

Castillo, Santos and Spoon are some of the roughly 1,092 AU alumni who have served abroad with the Peace Corps, according to the School of International Service.

AU is ranked among the top two schools for preparing Peace Corps Volunteers from mid-size universities and graduate schools. The School of International Service also offers a Peace Corps Prep certificate program for undergraduate students who are majoring or minoring in international relations.

Castillo taught deaf and hard-of-hearing children in information and communication technology at a school in Namibia. Wearing cochlear implants himself, Castillo’s experience inspired him to pursue a career related to deaf and hard-of-hearing education.

Despite leaving Namibia early, he still plans to pursue a master's degree at Columbia University in the Education of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing program starting in the fall.

Spoon said she hopes to be able to return to Indonesia with the Peace Corps and has delayed looking for a job or applying for graduate school in hopes that she can return.

Spoon, who holds a bachelor's degree in international relations and public health, initially considered pursuing a master’s degree in public health after her Peace Corps Service ended. However, the uncertainty around returning to Indonesia has put her plans up in the air.

“Until I get a definite answer that [going back] is not going to happen, I don't plan on looking for a real job because I really do want to go back.” Spoon said.

All of the evacuated Volunteers were given Returned Peace Corps Volunteer status, meaning they remain eligible for all of the benefits that they would have received had they finished their service. Those include non-competitive eligibility hiring status for federal government jobs for one year and the option to attend graduate school at a reduced cost through the Coverdell Fellowship program.

For Spoon, waiting to hear if she can return to her host country might cause her to lose her federal job eligibility status, but she said it’s a risk she is willing to take.

“I was only six months in, out of my 27 months, so I barely got a chance to get anything off the ground which was probably the most disappointing part.” Spoon said. “It was just a bummer. That was the biggest thing I could say about it because I finally felt like I was getting somewhere.”