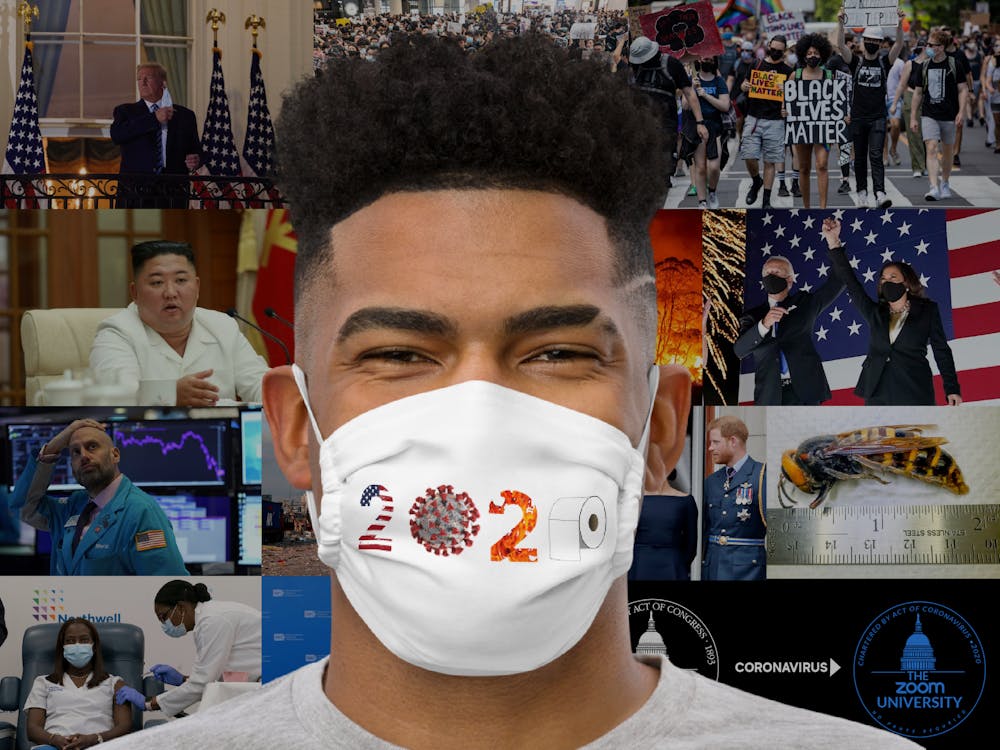

As people look back at the coronavirus pandemic, great economic fallout, reckoning over racism and political upheaval, it is evident that 2020 was a historic year for the United States. American University history professors discuss how they believe 2020 will be remembered.

“There isn’t one 2020, but many,” U.S. history professor Gautham Rao said. “It ultimately depends on one’s experience and understanding of the year.”

One of the defining experiences of the last year was the global pandemic. The world has seen over 113 million cases and counting, with the United States leading in both cases and deaths, according to data published by Johns Hopkins University.

Daniel Kerr, associate director of AU’s public history program, said he isn’t sure how the virus will be remembered, especially when looking back on the remembrance of previous pandemics.

“It is always hard to know how things will be remembered,” Kerr said. “We have certainly heard about the flu pandemic in 1919, but I don’t think people fully understood the severity of it until we experienced it this year. It could be that 100 years from now people will maybe remember the political history, and may not even understand the flu.”

Kerr said that people do not experience these crises evenly.

“During the pandemic, we saw the wealthiest becoming far wealthier while we saw significant levels of unemployment and economic deprivation,” Kerr said. “Therefore, acknowledging this divide is key to understanding how the future will study this period.”

2020 also saw a change in the nature of U.S. politics and social justice in light of historic events like the Black Lives Matter protests and the presidential election.

Donald Earl Collins, a professorial lecturer in the African American and African Diaspora Studies department, said that two groups of Americans became more radicalized as a result of the pandemic and George Floyd’s killing.

“One, young Black and Brown millennials, zillennials and white allies/accomplices are more engaged in U.S. politics and in fighting policies of marginalization and oppression,” Collins said. “Two, those who would and do make BLM and other social justice movements scapegoats for all of America’s ills, all while moving to disrupt and possibly destroy American democracy.”

Rao underscored the importance of oral histories in future teachings about 2020.

“The key thing to understanding any history is people, so in order to remember 2020, I would rely on oral histories to get a sense of how the pandemic affected different groups of people,” Rao said. “I would use obituaries, social media and even Netflix trends.”

Kerr’s COVID-19 project “From Me to You” collects personal testimonies in hopes to be used by future historians as a resource to understand the impact of the virus.

Kate Haulman, a professor of early North America and U.S. women’s and gender history, said since historians tend to think in terms of structures, systems and patterns that are longer-term, it’s too early to understand the impact of 2020.

“We can’t fully assess the changes with a historical perspective that we simply don’t have yet,” Haulman said. “Politically and culturally speaking, are we witnessing the end of something, the last gasp of a reinvigorated white supremacist patriarchy? Or, perhaps, unfortunately, a chapter in a longer story, but one that also features resistance and persistence?”