Editor's Note: This article appeared in The Eagle's March 2021 virtual print edition.

This summer, universities across the country reckoned with racism as protests erupted over the killings of Black Americans by law enforcement. Online and in-person, students pushed for institutional change, including the renaming of buildings and the replacement of statues that hold the names of controversial figures in history.

Princeton University removed Woodrow Wilson’s name from its School of Public and International Affairs, James Madison University renamed three buildings named for Confederate leaders, and Georgetown University announced in 2019 its plan to pay reparations to the descendants of the enslaved people the college sold.

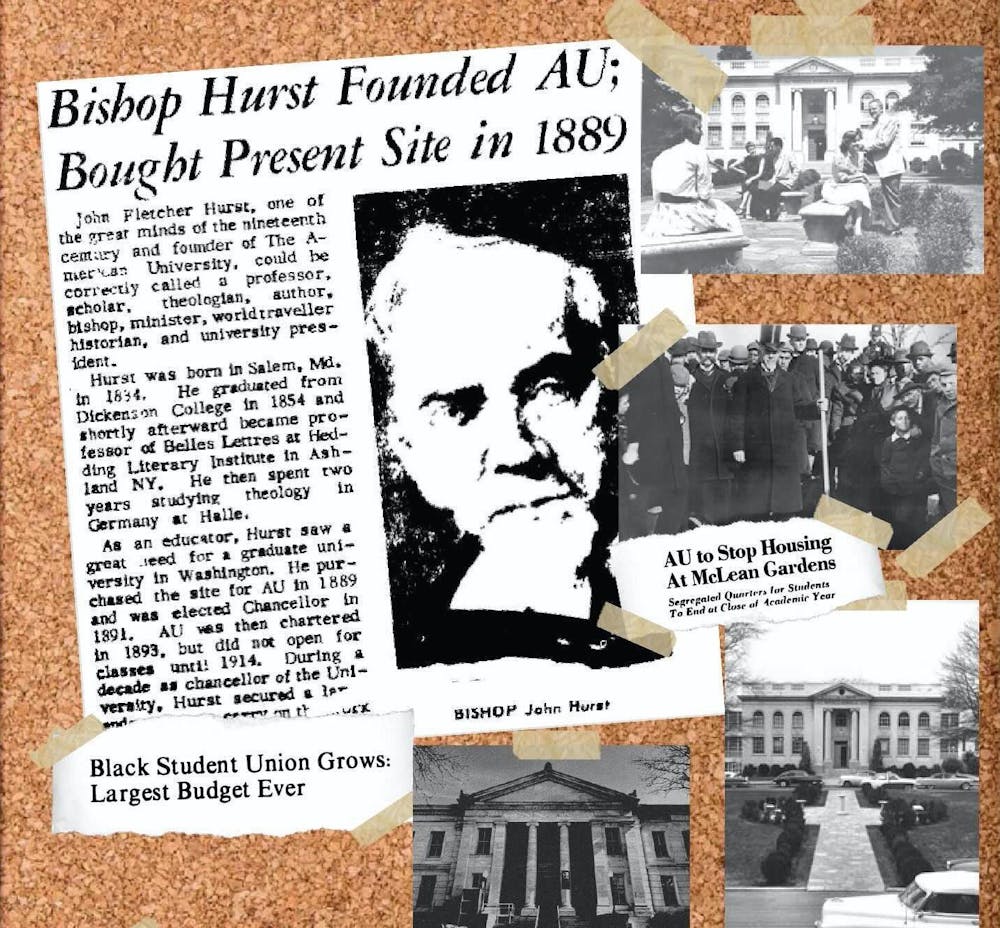

American University also has a building named after a man with ties to slavery –– Hurst Hall.

AU’s Working Group on the Influence of Slavery first presented its research on the University’s historic ties to slavery in spring 2019 and created an exhibit to showcase its findings. The group’s report states that John Fletcher Hurst, the founding chancellor of AU and a bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, inherited one or two enslaved people from his father. Hurst, who is immortalized on campus by way of Hurst Hall, freed his enslaved people at 16 after he entered the United Methodist Church, according to Sybil Roberts Williams, director of African American and African Diaspora Studies at AU.

The working group was created after Nickolaus Mack, former managing editor of the opinion section for The Eagle, wrote a column criticizing Founders Week for celebrating a founder that owned enslaved people. The community reaction to the original column was mixed and led the administration and student body to ask the question: What is AU’s connection to slavery and how were the University’s founders involved?

What’s in a name

Hurst Hall houses The Center for Teaching, Research, and Learning. The building’s namesake was instrumental in the founding of the University. Hurst also owned two enslaved people, both of whom he inherited from his father, said Williams, a member of the original working group.

However, Hurst authorized the release of Tom King, one of the enslaved people he inherited, to take place in 1862 upon King turning 21 years old, according to the working group’s report.

“Hurst did not have any active engagement with enslaved people at the time of the founding of AU,” Williams said.

Williams said that due to AU’s connection with the United Methodist Church, AU did not have any direct ties to slavery, however, funds were solicited from all over the country.

“Hurst didn’t [have enslaved people] but it is quite possible that some of the donors did.”

As universities across the country had their own reckonings with racism pasts last summer, AU remained quiet, leaving its work from the Working Group on the Influence of Slavery report a thing of the past before the group’s recent revival.

To rename or not to rename?

Mackenzie Meadows, a junior in the School of Public Affairs, was not aware of AU’s findings of Hurst when she took the Washington DC: Life in a Monument class in Hurst Hall.

“Why was that not brought up when we were creating a Black space on campus?” Meadows said.

Meadows is in favor of renaming Hurst Hall but said the work should not stop there.

She said there should be an increase in resources for Black Affinity Housing and more recognition of the history of Hurst for the campus community.

The Blackprint reported in spring 2020 that Roper Hall would become the new home for Black Affinity Housing starting in fall 2020. In February, Housing and Residence Life announced fall 2021 details for the program.

M.J. Rymsza-Pawlowska, the director of AU’s graduate program in public history and a member of the working group, said acknowledging history is more than just about the name of a building.

“I don’t see anything inherently wrong with changing things and renaming buildings,” Rymsza-Pawlowska said. “But I also think that that’s not enough that needs to be part of, you know, it’s not enough to take down a statue or to rename a building, you have to make sure that there are ways that people know why that happened and why it's important.”

Williams said that Hurst became an “ardent abolitionist.” She thinks if the hall is renamed, it should be Hurst’s name hyphenated with the names of the people he freed.

“He is integral to the founding of this University, but he is not Woodrow Wilson,” she said. “I do not think we need to go so far as the removal of Hurst, it just doesn’t rise to that.”

Williams was referencing Woodrow Wilson High School, which is in Tenleytown. DC Public Schools announced in September that the school would be renamed.

Fanta Aw, AU’s vice president of campus life and inclusive excellence and a member of the working group, said that renaming is not an action item of the group’s work and has not been discussed.

However, in the working group overview report “renaming buildings on campus” is a suggestion for ways that universities have acknowledged their institutional relationships with slavery.

Eric Brock, the AU Student Government president, who is a junior majoring in political science, said that AU’s approach to Hurst’s history was a “white savior narrative.”

“When you lift someone up to that status you are heroifying them in a way. So you’re saying, this is a person that we idolize, this is a person that was exceptionally well and good in the community,” Brock said. “And so when that has a name attached to someone who has ties to slavery or any system of oppression, that’s not really the best work for a university or any sort of community to uplift someone that is involved in such a wicked system.”

Fort Reno and forgotten history

Just north of AU lies Fort Reno Park, which offers views from the highest point in D.C. and is a former plantation. Fort Reno Park is also a former civil war defense and home to the only Civil War battle to take place in the District. Today, AU students are more familiar with the area it lies in as Tenleytown.

“Fort Reno and the surrounding area that AU was built on was once a large plantation,” according to Williams.

“It was Indigenous land before that and it was land we know was worked by African labor after that,” Williams said.

Purchased in 1853 and named “Oak Lawn,” the 62-acres that encompassed Fort Reno Park and the neighborhoods that surround what is now American University had “at least five enslaved people: Alfred, Sarah, Dallas, Mary and Rose,” Washington City Paper reported.

The land was destroyed in the Civil War and as the owners were incapacitated, their family hired developers to subdivide the property into 600 lots, dubbing it “Reno City.”

African Americans building a new life in D.C. and formerly enslaved persons were able to buy or rent property in Reno City.

After developers in the area faced pressure from the neighboring white subdivisions of Chevy Chase and Tenleytown, by 1951, the last residents of Reno City had moved and the segregated school in the community had closed.

Today, Tenleytown and the surrounding area of Friendship Heights are over 70 percent white.

“It’s a generational struggle”

When AU announced in the spring of 2020 that students would have the option to live in Black Affinity Housing, it was a victory for Black activists on campus, but it's not the first time such housing was instated.

In the 1970s, AU offered a previous iteration of Black Affinity Housing. Then called the “Black Cultural Floor,” it housed approximately 60 Black women and was home to students from all political ideologies and backgrounds, according to an article found in The Eagle’s archives.

Unbeknownst to many, AU offered segregated housing in the 1960s at McLean Gardens, an off-campus apartment building near the National Cathedral.

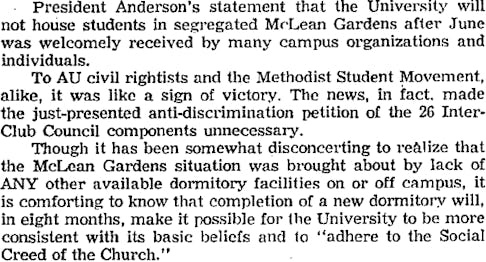

The decision to offer segregated housing was one made by McLean Gardens, not the University, according to articles found in The Eagle’s archives. Once students found out that the University was offering off-campus segregated housing, they fought the University. And won.

Rymsza-Pawlowska said that there isn’t much documentation of this part of the University’s history, which is likely why many don’t know about it.

In an article that was published in The Eagle in October 1961, The Eagle reported that AU President Hurst R. Anderson announced that the University would no longer house students in McLean Gardens.

“We know that AU was AU and D.C. was segregated and there is no way to excuse it but there is a way to say ‘yes it was here, racism was here,’” Williams said.

Brock said that the work of Black activists throughout the University is a “generational struggle.”

“It’s not something that started here or there, it’s not something that started in response to an individual incident, it shows that really the Black community, Black alumni, Black students, are interconnected in a way because our resistance, our call for Black Affinity Housing has been a generational struggle,” Brock said.

Moving forward and looking back

Students say that AU has a long way to better incorporate AU’s history into experiences at the University.

Williams, Mack’s former professor, has been at the forefront of trying to create new policy from the information learned in the working group report in the form of a scholarship for Black students.

“This has energized a whole discussion around affinity housing and what are we going to do for African American students now? How do we engage in affinity housing with bearing in mind the history of AU and that includes the history of African American presence at AU?” Williams said. “We started talking about what have been the contributions of African American students since African American students were first admitted [to AU]. And I hope with affinity housing we will be able to hold some kind of event that addresses that.”

Meadows agreed and said there should be an emphasis on resources for Black students, such as scholarships or continued advocacy for Black Affinity Housing.

“It should be escalated to the point where it reaches the current Black house being created on campus,” Meadows said.

Brock said that Black Affinity Housing is only one piece of the puzzle.

“Whether it was asking for the housing, or if it was asking for more funding for Black Student Union or for those sort of things for events, it shows that the Black liberation movement, the Black resistance movement on campus is dealing with in many ways the same issues,” Brock said. “And in many ways, it’s evolved. Because what once was segregation, is now just evolved to a different tool of anti-Blackness, whether it’s, you know, hate crimes or, or other violent means of racism.”