Correction: This story has been updated to clarify that “very few” people could preview the information, not an unknown number.

American University unintentionally exposed thousands of current and former students’ confidential information through the myAU portal, a violation of federal law, an Eagle analysis found.

The student information contained multiple sets of survey responses of current and former students conducted between 2015 and 2019. Also exposed were internal data showing the University’s prediction of individual student retention chances, although no financial, medical or academic information was accessible, according to Steve Munson, AU’s chief information officer.

The Eagle found that more than 4,500 individual students’ data was included in one or more of the documents, either labeled by name or AUID number. However, a University spokesperson said up to about 6,000 students’ information was exposed. Experts and the University say the information is covered by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, a federal law protecting education records.

Only those with credentials to log into the myAU portal — students, faculty and staff — had access to the records, Munson said. “Very few people” actually viewed them, although he declined to give a specific number. No one downloaded or exported the complete files, save The Eagle, a spokesperson said.

“American University takes the protection of our user’s data very seriously and deeply regrets that this data was exposed to other members of the AU community,” University spokespeople wrote in a statement to The Eagle. “American University is committed to the security of our data and systems and will continue to evolve our practices and controls to improve our security posture.”

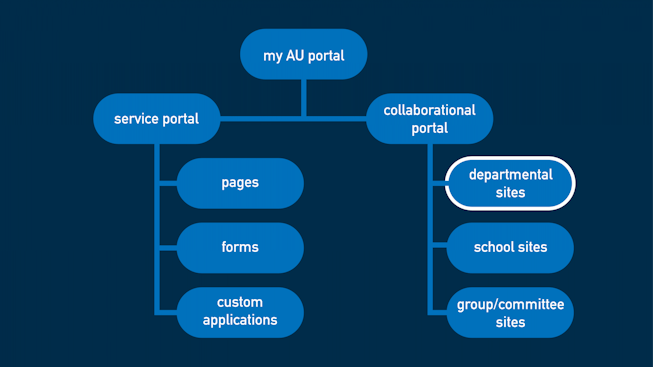

The information became accessible through human error in use of Microsoft SharePoint, a system underpinning the myAU portal, Munson said. The issues have since been fixed by the University.

AU will move to notify students whose information was exposed sometime in the next two to three weeks, according to University spokesperson Lisa Stark on March 17.

Upon notification of the incident by The Eagle, University staff revoked the incorrect access to student data and began a comprehensive review of access permissions within the SharePoint system, Munson said. The student data previously found by The Eagle is no longer accessible, according to an Eagle review.

What documents were exposed?

Since October 2019, documents with a variety of student information were accessible by anyone logged into the myAU portal, Munson said. In another case, a survey containing similarly protected student data was available to all student users for six years, ever since its creation in 2015.

All anyone had to do to find them was search for any name or number contained in the files.

Because of the way Microsoft SharePoint is designed, searches will return any information that the user has access to, even if it’s hidden somewhere they’d never think to look, according to Microsoft SharePoint expert Adam Levithan.

Based on The Eagle’s review, accessible data included a file containing Excel sheets with transition surveys from summer and fall 2019, a survey of incoming freshmen conducted at the start of the fall term between 2016 and 2018 and student retention data.

Accessible in the folder was an Excel spreadsheet entitled “Copy of Retention Predictions,” which ranked students by “attrition propensity” and identified them both by name and AUID number. According to Stark, retention predictions combine “information about the student and uses predictive modeling to determine a rough idea of the chance that the student might leave AU.”

“Generally, the survey data and retention predictions are used to help the university understand the aggregate factors related to students leaving AU and identify ways to improve the student experience,” Stark wrote in an email to The Eagle. “The only exception to this aggregated focus is the Fall Transition Survey. Students are notified when they take this specific survey that their responses will be used to identify support resources for them in an effort to aid their transition or improve their experience.”

The transition surveys, in the same folder with the retention data, both identified students by AUID number. The fall transition survey included responses to questions such as “Do you feel your professors care about you?” and “Did your high school prepare for the academic rigor of AU?”

The summer transition survey asked respondents to rank a variety of factors about how they felt about their move to AU, including their excitement, whether they expected to eat and sleep well and how much financial aid impacted their choice of school.

Another Excel sheet contained the results of a survey of incoming freshmen at the start of fall terms 2016, 2017 and 2018, according to Stark. It listed respondents by AUID number.

In a separate part of SharePoint, student users could access a survey of students who considered leaving the University, which included responses to questions such as “When did you first consider leaving AU? If you’ve decided to leave, how certain are you in your decision right now?” Here, students were identified by name. The survey was shared with individual students intentionally to get their responses, but answers were unintentionally made accessible to all students, according to Munson.

The fact that both the retention data folder and the separate survey were accessible was random, Munson said — they were not governed by the same permissions.

“It’s two different root causes,” Munson said. “It is interesting that they’re both survey data, but that’s more of a coincidence, I would say.”

The Office of Information Technology (OIT), which oversees the portal, can see who accessed files and documents and whether they downloaded them, Munson said. According to an internal review conducted by the office, “very few people” ever opened the documents in question beyond authorized staff or The Eagle.

However, if users searched for terms contained within any of the relevant files in the portal, they may have been able to “preview” small amounts of information by hovering over the search results, Munson said. He believes the possibility doesn’t pose a significant risk to student data due to the limited scope of SharePoint’s preview function, and said that “very few” people have done so.

Potential consequences

The exposure of student data isn’t just a violation of University policy.

While it didn’t include sensitive personal information, such as Social Security Numbers, it still contained AUID numbers, names and survey responses, and is therefore classified as educational records. That means it’s covered by FERPA, the federal law administered by the U.S. Department of Education that prevents the release of protected student information without the consent of the student.

According to LeRoy Rooker, a leading FERPA expert, access to such records is generally prohibited unless the viewer is a school official with legitimate educational interest or the relevant student provides signed consent for access to their records. Rooker previously spent more than two decades as director of the Department of Education’s Family Policy Compliance Office, overseeing FERPA.

Educational institutions that receive funding from the Department of Education agree to abide by FERPA, which limits access to student education records, including grades, financial information, ID numbers and more. According to Rooker, if institutions don’t comply with the department and investigate the error, they could lose all funding from the department.

The odds of that consequence are low, Rooker believes; no university would ever willingly put itself in the position to lose funding. Once The Eagle informed the University of the incident, it reached out to the Department of Education and “indicated to them what we were doing to correct the situation,” Stark wrote in an email to The Eagle.

“The Department will determine if there’s been a violation, and then say ‘here’s what you gotta do to be compliant,’” Rooker said. “If they do, then there would not be further action. … That’s the whole thing about FERPA: the institution is responsible.”

In a February statement to The Eagle, a U.S. Department of Education spokesperson agreed.

“While the Department has a number of enforcement actions, the Department is required by statute to work with educational agencies and institutions to bring them into compliance with FERPA before taking action to terminate funding,” they wrote.

While FERPA doesn’t require that institutions implement specific security protocols, it does require that they use reasonable methods to safeguard student records, said Anisha Reddy, an expert in youth and education privacy at the Future of Privacy Forum. FPF is a Washington, D.C.-based think tank and nonprofit group that focuses on issues of data privacy.

“It’s easy to have policies on paper and then it’s a matter of making sure there’s follow-through, there’s training and consistent messaging,” Reddy said.

Students’ main course of redress would be to file a complaint with the Department of Education’s Student Privacy Policy Office saying they believe their institution violated FERPA, Reddy said. The office could then initiate an investigation. She agreed with Rooker that a loss of funding is unlikely — after all, “stripping away funding from a school is not something that anyone wants to do,” she said.

“If their data is being mishandled, they should have a means for redress, right?” Reddy said. “I think it also comes down to finding the root cause of why this happened. I do believe that administrations and school administrations do have the best interests of their students at heart, and it’s really complex, especially now with how much data that schools can be collecting.”

Beyond appealing to the Department of Education, though, Reddy said that students’ options for recourse are limited. Under FERPA, there’s no private right of action, meaning students can’t directly bring a lawsuit against the University for the exposure of their data.

“It's a stretch, but students can look to ‘privacy torts’ — however, academics have long argued that current understandings of privacy torts ineffectively translate to the digital realm, and should be updated,” Reddy wrote in an email to The Eagle.

The Department of Education did not respond to multiple requests for comment on AU’s handling of the data, but when initially contacted by The Eagle in February, a spokesperson said they’d be unable to determine whether a FERPA violation occurred without beginning an investigation.

“Whether the scenario conveyed in your inquiry would be ‘a violation of FERPA’ is predicated on the totality of the facts in the case,” the spokesperson wrote in an email to The Eagle. “If an eligible student were to file a timely complaint with the U.S. Department of Education (Department) that indicated his or her rights under FERPA may have been violated, we would consider the complaint and could initiate an investigation.”

This isn’t the first time that a university using Microsoft SharePoint has unintentionally violated FERPA. In 2017, the OU Daily at the University of Oklahoma reported that similarly lax sharing permissions led to the exposure of thousands of students’ grades, financial information and Social Security Numbers.

In AU’s case, however, Munson believes that no student information beyond the survey results and related Excel files was exposed.

“This is not a tip of the iceberg situation — it does appear to be very isolated,” Munson said.

How it happened: the technical side and “human error”

Microsoft SharePoint experts Adam Levithan and D’arce Hess said the problem was likely rooted in permissions and sharing settings. Neither viewed the data or interacted with the portal and only acted as outside experts and consultants.

The core of SharePoint is its permissions structure, Levithan said. That structure is controlled primarily through groups created by an institution’s IT department that identify users as students, instructors or whatever other role the institution needs, which then determines their ability to access files and document libraries.

Hess said that permissions can be as broad or specific as need be, especially with the smaller SharePoint groups.

Permissions are inherited, so when documents are added to a folder already shared with a group, everyone in the group can view and interact with those documents, according to Hess. That is true all the way up the chain to the large sites at the top of SharePoint.

The other way SharePoint is controlled is through content sharing. This effectively cuts through the inherited permissions of SharePoint groups by allowing users to directly share documents with one another and can be easily misused due to SharePoint’s design. Often, when a staff member shares a file with another user, they can inadvertently share it with an entire group that that user is part of, Levithan said.

Departments within an institution often operate independently of each other on sites within SharePoint, Hess said, which, speaking generally, are often run by staff not trained from the ground-up in SharePoint.

“Oftentimes, departments or groups of people that are given a site where they store documents or store information ... are not well versed in permissions and how you make sure that people don’t get to things,” Hess said. “Oftentimes, they’ll try to store information there, not realizing that other people could potentially be able to get through using search or just seeing it.”

Levithan agreed.

“Without practice, the specific minutiae of these systems are easy to forget,” he said.

That’s similar to what happened at AU, according to Munson. Based on logs that track user activity, both the folder containing the retention information and transition surveys and the separate transfer survey were made accessible to “global audiences” — large groups that classify students, faculty and staff — shortly after creation or immediately upon creation, respectively.

Munson believes the permissions adjustment was inadvertent, probably done by a staff member who didn’t fully understand what they were doing.

“It was within an OIT folder and it was a folder within our business intelligence team, and somehow this permission group got added to that folder — the one that gave the access,” Munson said. “We can see in the logs when it was added, but we can’t see by whom it was added. We do expect it was a member of the project team.”

However, it’s not possible to say for certain why, although Munson doesn’t believe it was malicious.

“We believe it was a mistake, and that an individual was adding security to the SharePoint site and picked this particular group and added it and did not realize that what they were adding was the rights for everyone to access it,” Munson said.

He doesn’t believe it was a training failure, though. Instead, he termed it “human error.”

Reddy, the privacy expert, doesn’t necessarily agree.

If issues crop up in data security and mistakes continue to be made, like with the much more common threat of phishing attacks, “it’s no longer human error, it’s a matter of the training,” she said. “I think that applies to when you’re building a system as well.”

Moving forward

While AU has maintained security meant to handle external threats to student information for years, and OIT regularly handles software updates and general user maintenance, Munson said that regular audits of user permissions were only planned to be implemented this year.

This incident sped up the timetable.

The lack of regular permissions audits is normal among organizations using SharePoint, Levithan said. AU isn’t unique in that regard.

Now that staff can say that the permissions issues have been solved, they’re going back and doing a more thorough audit of the global audiences — the large groups that include students, faculty and staff. Munson said this is part of the first periodic review the team will conduct moving forward in an attempt to prevent future violations.

The reviews will involve examining the permissions of folders and verifying with relevant staff that everyone who can access their documents is supposed to, Munson said. They’ll pay especially close attention to surveys like the transfer one, as those are often shared with students to get their responses.

“To mitigate these issues from occurring in the future, OIT is implementing a periodic, automated review and reporting of our SharePoint sites to proactively identify situations where sites or folders are available to audience based groups such as all users logged into the myAU portal, all students, all faculty, all staff or a combination of these groups,” AU spokespeople wrote in their statement.

Once site permissions and surveys are audited, the team plans to look at more granular permissions. These risk areas will be regularly reviewed moving forward, Munson said.

Sometime in the next two weeks, AU plans to reach out to all students whose information was accidentally exposed, Munson said. They plan to provide each person with specific details about their data, rather than a blanket statement.

“We’re doing the analysis that basically says, ‘this person’s data was in spreadsheet A, but not B, or A and C, but not B,’” Munson said. “We’re trying to be as precise as we can and as specific as we can to describe the data.”

It won’t just be technical information, though.

“Beyond that, we will emphasize our commitment to keeping data secure and we will communicate that we apologize that this had occurred and that we’re here to answer any additional questions that they may have,” Munson said. “We take this very seriously.”

“This would be an example where we didn’t live up to our standards and commitment.”

The Eagle accessed and downloaded student records for the reporting of this story. Individual names of students or AUID numbers will not be shared or reported on. The three staff members who viewed student records deleted all screenshots and documents from their computers before this story was published.

If you are contacted by AU regarding the exposure of your information, please consider reaching out to Campus Life editor Dan Papscun, dpapscun@theeagleonline.com, for a follow-up story.

Spencer Nusbaum contributed reporting and analysis to this story.