Imani Barbarin knows what it’s like to have tough conversations.

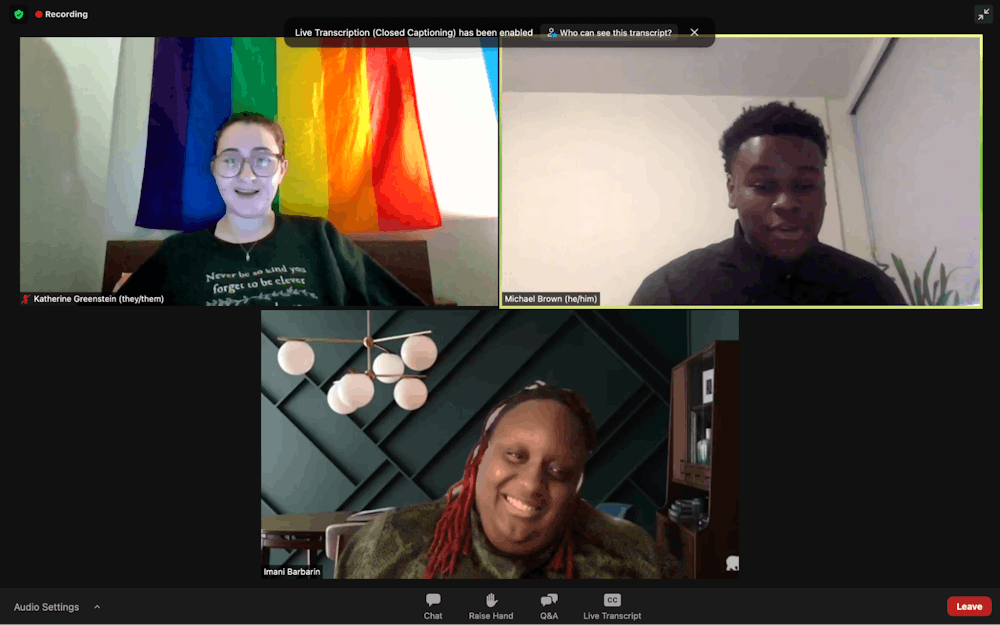

The disability rights and inclusion activist spoke at a webinar co-hosted by the Disabled Student Union, American University’s NAACP chapter, the Kennedy Political Union and the Women’s Initiative on Feb. 23. The conversation, moderated by DSU President and School of Public Affairs sophomore Katherine Greenstein and Vice President of the AU NAACP chapter and junior Michael Brown, centered on Barbarin’s experience navigating what she described as social and institutional failures to provide for disabled people like herself.

“We have to live this life all the time, and oftentimes we are beholden to laws that keep us poor, keep us isolated and keep us alone,” Barbarin said.

Barbarin has used her perspective as a Black disabled woman to advocate for the disabled community through her writing and social media platforms. One of her main goals, she said, is to spread awareness about the intersection of race and disability.

“I think it is incredibly important that we really investigate different axes of oppression and marginalization in order to facilitate a society that works for us all,” Barbarin said.

Barbarin discussed her personal experience living with a disability and how the Black disabled community has been impacted by the coronavirus pandemic.

Barbarin explained the role that racism has played with the perception and acknowledgment of disability in the Black community.

“We have to remember that a lot of our history is oppression on the basis of race through disability,” Barbarin said. “During our enslavement, slaves who were disabled were often either killed off, starved to death or sold to freak shows, carnivals, things like that. So our history is tied greatly to our ability to survive.”

Barbarin said this connection between disability and oppression highlights how ableism has historically been used as a tool of white supremacy “to make race more tangible.”

“Ableism has been the avenue through which we have eradicated people,” she said. “[Ableism] has meant race science, which is the science of diagnosing otherness via race as a disability, trying to find physical characteristics or physical impairments that explain Blackness … All of these different things are disabling in order to perpetuate white supremacy.”

This concept is one of many that Barbarin has sought to spark discussions about through her blog Crutches and Spice and podcast of the same name. In addition to serving as a communications director for the nonprofit Disability Rights Pennsylvania, Barbarin has been published in several publications including Forbes, Rewire and Healthline.

Much of Barbarin’s impact has been made through her social media presence. With more than 100,000 followers on Twitter and over 150,000 followers on TikTok, Barbarin has created more than a dozen trending hashtags that give other members of the disabled online community a chance to share their stories and call attention to the problems affecting them.

“I like hashtags because I feel like it’s a good place for us to all filter into the exact same place what we’re feeling,” Barbarin said. “It lends credence to our emotions in that moment.”

One of Barbarin’s most famous hashtags is #MyDisabledLifeIsWorthy, a TikTok and Twitter trend that she created at the end of 2021 in response to a statement from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, who called data showing that 75 percent of COVID deaths occur in people with four or more comorbidities “encouraging” in a December appearance on ABC’s “Good Morning America.”

“I think the disregard for human life just got to me because even when [the COVID-19 death rate] is a statistically low number, that’s still somebody’s life,” Barbarin said. “I started the hashtag because I felt like, throughout the entire pandemic people really discounted what our lives mean. And I personally believe there’s inherent dignity to everyone.”

Even after Dr. Walensky issued a public apology, Barbarin felt that the damage had already been done.

“The language change is fine, but the sentiment behind it is what is concerning because language is just a manifestation of an inherent belief,” Barbarin said. “It’s not necessarily that she changes her language, or the CDC changes their language, it’s the thought process behind them and the people who are put into power to make that thought process happen.”

According to The Health Foundation, six out of 10 people who have died from COVID-19 are disabled. The CDC also states that people with disabilities are more likely to get infected or have a serious illness because of underlying medical conditions and systemic health inequities, a problem that Barbarin said she has anticipated since the start of the pandemic.

“I remember hearing rumblings about COVID in Italy and Wuhan, and they kept reporting that it was primarily [affecting] elderly and immunocompromised people,” Barbarin said. “The focus on that was really concerning to me because I knew that people would shut off if that was the messaging.”

Combining her social media presence with activism, Barbarin took to TikTok to warn others of the consequences the pandemic would have for her community.

“I think my second TikTok on the platform was me warning Black folk,” she said. “I was trying to warn people that this will hurt us disproportionately, and at the time I was right.”

Despite the grim situation, Barbarin is still looking forward to the future. She hopes to continue projects that were interrupted by the pandemic, such as a television series about dating while being Black and disabled. She also wants to see systemic changes for her community, with an emphasis on a push toward universal healthcare.

In the meantime, however, Barbarin said there are things that non-disabled people can do in their day-to-day lives to help reduce inequities.

“The first thing you can do is just look around,” she said. “Advocacy is not always going to be harassing politicians or creating campaigns. Sometimes it’s just looking at a crack in the sidewalk and being like ‘Hey, can somebody fix that?’ There are little ways in which you can change somebody’s life drastically.”

Barbarin added that simply listening to members of the disabled community can be game-changing.

“Doing the actual work to understand what they’re saying and not passing judgment on them is the work itself,” she said. “You want to be able to absorb feedback in a way that empowers them to speak more broadly about their experiences.”