D.C.’s Ward 5, a predominantly low-income and black community, contains 1,030 acres of industrial zoned land. For decades, these industrial facilities within this area have been known to cause air pollution and subsequent health issues, but residents of one neighborhood, Brentwood, have decided to challenge this.

The District Department of Transportation plans to build a bus depot in the northeast D.C. neighborhood. Residents of Brentwood filed a lawsuit against the construction of the bus depot in 2021 because they believe the bus depot would contribute to increased air pollution in their community.

Residents of Brentwood are working with College of Arts and Sciences Professor Valentina Aquila and second-year School of International Service graduate student Lynn Heller to receive a “quantifiable assessment of what is the air pollution in the neighborhood,” Aquila said. The residents plan to use Aquila’s data in an appeal of their court case in the fall of 2022, since their case filed in 2021 was dismissed due to lack of standing.

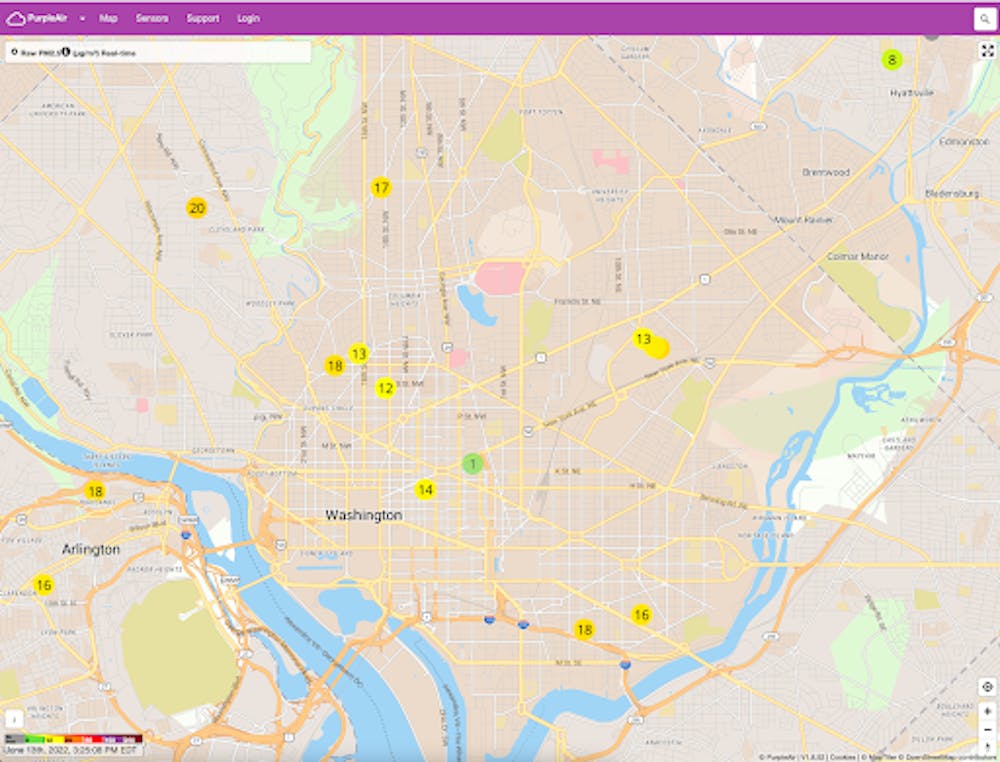

To collect the data, Aquila and Heller installed air pollution monitors throughout D.C. that measure the concentrations of particulate matter in the air, such as dust or carbon. These monitors are installed both inside and outside of homes. They are low-cost and can be checked by Brentwood residents hosting the monitors in real-time.

“We can explain to the residents how the sensors work, what we're measuring and share with them the map, so they can go online and see, this is the air quality at my house. There's a number here, there's a meaning here. Explaining to them communicating the science behind what we're doing. That's really exciting for me,” Heller said.

Heller not only collaborates with Brentwood residents, but also nonprofit organizations such as Empower DC: an organization working with the residents of Brentwood to help them take legal action. The mission, according to the website, is to “advance racial, economic and environmental justice.” Empower DC also coordinates with scientists from other organizations and universities that measure other components of air pollution in Brentwood such as greenhouse gasses.

Aquila and Heller also attend meetings with Justice for Brentwood, a group organized by the residents of Brentwood, to discuss the research’s progress and look for more volunteers to host monitors.

Besides collecting data on air quality, another component of the project focuses on health assessment surveys, since air pollution is prone to cause health issues such as cardiovascular diseases or asthma.

Aquila and Heller plan to use their particulate matter measurements and compare them with measurements taken by EPA monitors in other areas of D.C. EPA monitors are higher quality and more expensive instruments compared to the low-cost monitors they are using, according to Aquila. At the end of the summer, Aquila and Heller plan to complete a write-up of the particulate matter measurements and health assessment results that the residents can use in their court case.

Heller hopes their report can provide the Brentwood community with essential information about the quality of their air. Whether or not the report will show there is a problem with the air quality is still unknown. The report also may impact industrial planning that could affect the community’s health and safety.

“I have no idea what we're going to find. I'm very hopeful, you know, that maybe this project just brings the people of Brentwood some kind of peace of mind,” said Heller.