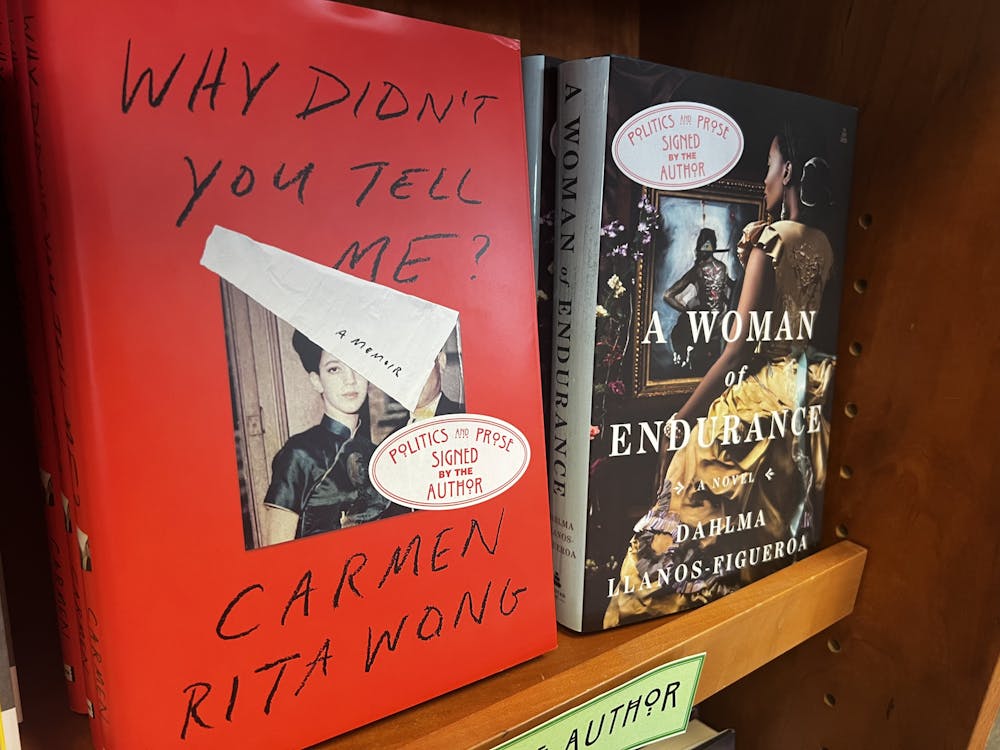

Telling the stories not told. Sharing lived experiences, previously kept in the shadows. These were two goals of authors Carmen Rita Wong and Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa when they wrote and published their books, “Why Didn’t You Tell Me?” and “A Woman of Endurance,” respectively. On Sept. 18, Politics and Prose hosted a Latinx Caribbean Heritage Panel with Wong and Llanos-Figueroa, who spoke on their writing and how it is deeply rooted in history, finding peace and diverse representation.

Both authors wrote their stories to highlight their shared Caribbean heritage and individual multifaceted identities. In an interview with The Eagle, Wong shared one intention she had when publishing her memoir.

“This is America, to quote Childish [Gambino]. That’s it. I wanted people to very specifically hear a multi-generational story from a woman of color. How the generations in this country have been shaped by politics, race, gender identity — all of these things — and really coming away and really understanding what is the life of immigrants from say, the 1950s through now,” Wong said.

Llanos-Figueroa also wanted to emphasize acknowledging her ancestors' history and writing her novel as a way to add something new to the public narrative.

“I feel that we have many stories not told. I feel that many people in our society are faceless and voiceless, and certainly, Afro-Puerta Rican women are one of those,” she said. “I felt like I had to give a voice and a face to my ancestors and to people who look like me. Without them, we would not be here.”

“Why Didn’t You Tell Me?” begins in childhood living with Wong’s Latina mother in Harlem and in Chinatown with her immigrant father. Later, Wong moved in with her white stepfather to attend a predominantly white Catholic school in New Hampshire, and when she is older her mother reveals long-held secrets without giving Wong the chance to ask the book's namesake question. “A Woman of Endurance” is set on a 19th century Puerta Rican plantation, where a spiritual African woman was kidnapped and enslaved with the intention of forcing her to have children who would also be taken and sold into slavery. Both novels unpack the complex and sensitive concepts of motherhood, practicing religion, the feeling of being “othered,” finding a sense of belonging and the harmful actions people are capable of toward others.

Wong said that she lived her mother’s reality for 31 years and that it was her turn to “have the mic.” She elaborated on fairness and honesty, saying that memoirs are about that person’s “pain” and “lessons learned,” and that it “only belongs to you.” Still, she said she wanted to be sensitive in portraying the adults still present in her life.

“I was very respectful in the sense that there were no villains. In families you can’t paint people as villains or else they're not human beings. To make someone a villain is to dehumanize them… that’s why I wanted to be very fair,” Wong said.

The process of writing the books was incredibly involved for both authors. Llanos-Figueroa said that she did significant amounts of research including going to Puerto Rico and speaking with people whose grandparents and great-grandparents were enslaved.

“It probably took about six years to write and then another two or three years to find a publisher,” Llanos-Figueroa said. “I think the Black Lives Matter movement brought to the forefront the fact that there are many people in our society who are the ‘other’ who are actually part of the definition of American.”

Barriers were lifted and an opportunity presented itself for “A Woman of Endurance” to be received. However, Wong seemed to have indicated that her work took a long time to write not because of societal issues, but more through personal struggles. During the process of bringing her vision to life, Wong said that she had to let go of several agents “because it’s very important for your representation to at least jive with your vision and understand you as a human being and what you're trying to do,” she said.

Both Wong and Llanos-Figueroa had very clear and somewhat similar messages on why they wanted their books to be read and what they wanted to convey through the publishing of each respective story.

“I wanted everybody to read the book. And not because of sales, but because I believe that everyone can relate to it,” Wong said. “I've had people write me; I’ve had white men write me; I’ve had gay women write me; I’ve had Black, Latino, Asian, Indian — I've had every kind of person, seniors to young women say ‘I see it, I felt it, I’m not even the same culture but I know what that feels like’ … I just wanted to touch as many people as possible.”

Keeping along with the theme of reaching a wide audience and helping people reflect and learn, Llanos-Figueroa agreed with Wong.

“I think we live in a very polarized society where people are accusing each other and are hateful towards each other,” she said. “I wanted to create a work of art that allowed us to open a discussion about the issue of race and slavery and power, without it degenerating into you and me and blaming each other. But rather looking at the concept and having a discussion about how we got to where we are today.”