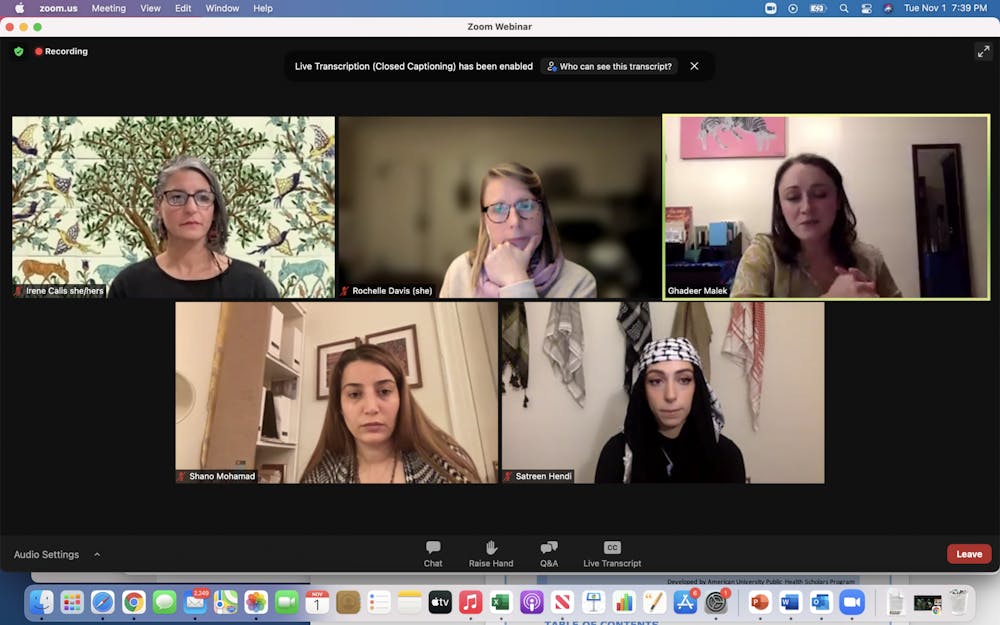

Palestinian writer and spoken word poet Ghadeer Malek shared her work in an online event hosted by American University’s Arab World Studies and Georgetown University's Center for Contemporary Arab Studies on Nov. 1.

During the discussion moderated by AU Director of Arab World Studies Irene Calis, Malek talked about tackling subjects like displacement, feminism and settler-colonialism as a Palestinian woman. The talk also included poets Shano Mohammed, a Georgetown student in the Master of Arts in Arab Studies program, and AU student Satreen Hendi.

The event is the second installment of the online speaker series, “Palestine: Land, Life, Dignity,” a collaborative initiative aimed at centering anti-colonial struggles and protecting similar stories from erasure. Malek said portraying this reality and relating it to a larger picture is the basis of her work.

“What drove me to poetry was the need to express ourselves as Palestinians in particular,” Malek said at the event. “I always joke around with my friends that Palestinians are gaslit from the moment they’re born in the sense that … we’re born into a reality in which [our experience of colonialism] is completely erased.”

Malek added that poetry, specifically spoken word, has become a vehicle for expressing her anger and resilience at the damage colonialism has inflicted on Palestinian and other Indigenous communities.

“A lot of my voice at the beginning came out as rants because I was angry as a young Palestinian; angry at the world, angry at colonization,” she said. “I wanted my voice to be heard … and that sort of anger was channeled into spoken word.”

Born in Palestine, Malek immigrated to Canada in 2003 to study at the University of Toronto, where she became active in student movements supporting Palestinian causes. Her body of work includes the poems “I Exist,” “Revolution to My Earth” and the anthology book “Min Fami: Arab Feminist Reflections of Identity, Space & Resistance,” a collection of writing from multiple authors. Malek said having multiple voices was an integral part of the book.

“The more voices that come to the table the better they are,” she said, adding that gathering writers from various religious and cultural backgrounds helped her form a community. “That’s why I’m very proud of ‘Min Fami’ … I don’t feel like I’m a single voice talking on my own.”

In an example of gathering different voices, Mohammed and Hendi both shared poems about overcoming cultural and institutional barriers. Mohammed, who was born in Iraqi Kurdistan, recited her poem about the limitations placed on women in the Middle, East and Sateen delivered a poem centered around the death of Shireen Abu Akleh, a Palestinian journalist killed by Israeli police in May.

“This is one of my process pieces where I start with an idea or a phrase or something and see where it takes me,” Hendi said. “I talk about the frustration of what it feels like to have to deal with the trauma and the pain of experiencing that situation in real time while also trying to convince people to care about it.”

While spreading awareness about difficult topics is a central part of her work, Malek said she still grapples with self-doubt about her identity and qualifications as a writer.

“It’s always a lot of questions and a lot of hesitations in the sense that there’s always a voice underneath our voice … there’s always another voice there questioning,” she said. “I like to call that voice the doubtful voice, the colonizer’s voice, the oppressor’s voice telling us that we’re not good enough.”

Malek said she combats these feelings by reminding herself, and other Palestinian activists, that her lived experience is more powerful than her doubts.

“Follow that voice of what you know, because when you write about what you know, the hesitations will still be there … but you can override that voice because you know something that voice doesn’t know, which is that you’re Palestinian,” she said. “Always acknowledge that that voice will come, but you have an inherent knowledge that you can tap into.”