Editor’s Note: Jordan Young, The Eagle’s managing editor for news and a member of DSU, was not involved in the writing, reporting or editing of this story.

Already late for class on the first day, Madeline Caballero rushed into the Watkins Building. Legs and ankles already aching from hauling herself out to the sociology building, she didn’t trust herself on the stairs. Caballero has a connective tissue disorder and an inflammatory autoimmune disease, both of which result in chronic pain. For this reason, it’s often difficult for her to safely navigate staircases. So, instead of risking a fall, she asked someone where she could locate the elevator.

“And he just said to me, ‘No, there isn't one,’” Caballero said. “I was just stunned.”

Caballero is not the only American University community member that has struggled with the campus’ accessibility. Tanja Aho, a professorial lecturer in the Department of Critical Race, Gender & Culture Studies, has engaged in many conversations with students, employees and administrators about access and inclusion for community members with disabilities. Aho co-founded the Disability+ Faculty and Staff Affinity Group to help support faculty and staff with disabilities and found that there are many community members who struggle with accessibility issues on AU’s campus. These issues range from building accessibility to accommodations and information resources. According to Aho, the effort to address those concerns is ongoing.

Building Accessibility

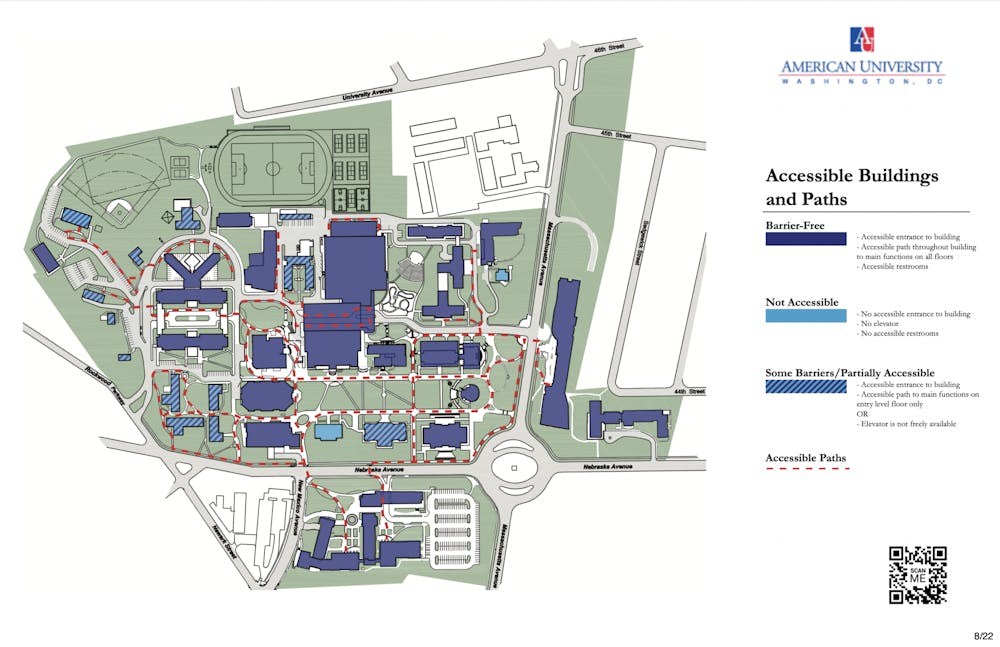

According to the accessible pathing map provided on AU’s website, there are 15 buildings on campus that are either partially or totally inaccessible. While there are laws about building accessibility, according to Robert Dinerstein, a professor of law and the director of the Disability Rights Law Clinic at the Washington College of Law, those laws don’t specifically require all buildings to be accessible.

Instead, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 requires that all students and employees have equal access to programs at any educational institution receiving federal funding. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 requires buildings to meet accessible standards only if they are built or substantially renovated after 1990.

“So you’re required to give people equal access to the program, but not necessarily to the specific site,” Dinerstein said.

Caballero, who is in a post-baccalaureate pre-medical program in the College of Arts and Sciences, said she has frequently struggled with building inaccessibility on AU’s campus. According to Caballero, her disability creates ankle instability that makes it difficult and dangerous for her to use stairs. She said she has twice arrived at buildings on the first day of classes only to realize that there wasn’t an elevator for her to use.

“To have one experience with that would be unacceptable,” Caballero said. “To have that happen twice is really … I don't really have words for how shameful that is. And that says how AU treats its students with disabilities.”

According to Dinerstein, there are limited ways to encourage institutions like AU to address building inaccessibility. Unless there are substantial renovations to a building, the only way that accessible changes are made to a building is at the discretion of the institution or as a result of a lawsuit.

However, according to Aho, most students don’t have the capacity to push the University to make that change.

“In order to sue the University you need money, you need resources, you need knowledge and you need time,” Aho said. “And students usually have maybe one of those four things, but often they don’t have any of them.”

Student Accommodations

Student accommodations generally fall into two categories — academic and non-academic. Academic accommodations are handled by the Academic Support and Access Center and involve changes to students’ learning or testing environments.

The number of students seeking academic accommodations has increased by almost 25 percent in recent years, according to Jessica Waters, the dean of undergraduate education and vice provost for academic student services.

Students who are neurodivergent or have a physical disability can receive academic accommodations via a three-step process that is outlined on the ASAC website. Those three steps include filling out a student accommodations questionnaire, submitting documentation of disability and then working with an assigned disability access advisor to review documentation and finalize accommodations. In the event that a student, upon receiving their accommodations, does not feel that their needs are being met, can then undergo the Reasonable Accommodation Reconsideration Process. If the appeal is further denied, then a student can submit a Reasonable Accommodations Grievance that is sent to the 504 coordinator for students, Seth Mancini, who is also the faculty relations investigator.

Non-academic accommodations encapsulate all other areas of campus not under the purview of academic departments, whether that’s the paths on campus or shuttle services. This is with the exception of housing accommodations, which ASAC assists with. For non-academic accommodations, students must contact relevant staff or administrators for the area in which they need the accommodation.

According to Aho, the system of accommodations is not the most accessible way to support students and community members, because of the work it asks them to take on.

“We also have the ongoing reality that we are working on an accommodations-based model, which means that we are trying to shift the burden of access onto individual students instead of thinking more about what kinds of accessible environments we can create, generally speaking, so that everybody can flourish,” Aho said.

Even within the accommodations model, Caballero said she has frequently run into issues when trying to receive support. She has had her academic accommodation requests denied or revoked by ASAC many times in the two years she has attended AU, sometimes resulting in physical pain and academic fallout, she said.

Caballero has faced issues ranging from being provided inadequate materials after she requested ergonomic seating, resulting in severe pain during testing, to having to withdraw from a class after her accommodation for a peer note taker, which she had through high school and her undergraduate degree, was revoked.

“The experience I have had with ASAC has been utterly traumatic and difficult beyond belief,” Caballero said. “I can not tell you how many problems I've had with ASAC. I'm still having problems with ASAC.”

Henry Jeanneret is a junior in the School of Communication and CAS and is the president of the AU Disabled Student Union. He said he frequently advocated for students who had accommodation requests denied when he served as the DSU’s ASAC liaison. According to him, many students have dealt with these issues.

“I don’t know what the rates are of people getting denied in terms of accommodations, but it happens enough to where it's a major problem,” Jeanneret said. “Most people in DSU do not like ASAC and do not trust ASAC.”

Faculty and Staff Accommodations

Faculty and staff accommodations are handled entirely separately from student accommodations and are separate from ASAC. Workplace accommodations for employees are handled through the human resources department after an employee submits a Reasonable Accommodation Request Form.

While this system is in place for faculty and staff with disabilities, according to Marc Medwin, an assistant professor in the Department of Performing Arts and co-chair of the Disability+ Faculty & Staff Affinity Group, information about resources and accommodations isn’t always communicated to faculty.

“I think accommodations for faculty, and this is again my experience, needs to be streamlined a little or at least explained more completely to the faculty as they come in,” he said.

Medwin is blind and is entitled to a blueprint at the front of his classroom that shows how furniture and materials are supposed to be laid out. Yet, according to Medwin, that accommodation isn’t strictly adhered to. He said he often faces difficulties navigating the building he works in, the Katzen Arts Center, and his classroom due to people moving furniture and leaving things in the hallways.

“This is something that I have actually brought up over the years and it's gotten better, maybe, but I can’t count on it,” he said. “And that only takes one instance, you know, to either make you start class a little bit late or to … cause an injury.”

Improving Accessibility

Waters, alongside Assistant Vice President of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Amanda Taylor, spearheaded a workstream in 2021 to address the needs and concerns of students with disabilities.

According to Taylor, the workstream has made a wide array of recommendations so far. Those recommendations included having a dedicated ASAC staff member that works with WCL students, increasing the number of staff in ASAC, creating a new role to look at how to support disabled community members and formulating plans to keep the campus accessible during construction. They have also worked on educating faculty about creating inclusive classrooms, developing a relationship with DSU and working with the Office of Information and Technology to make online resources more accessible.

“These are continuing conversations,” Taylor said. “Some of the action items, as we talked about, have already been implemented. And others are kind of deeper dive conversations that are still very active.”

In addition to the efforts of the workstream, according to Waters, ASAC has implemented a number of new policies that are meant to alleviate accessibility barriers. Students can now use documentation provided by AU’s Center for Well-Being and Psychological Services to support their accommodation request, as opposed to needing an external clinician. ASAC testing proctors have also been given access to Canvas pages in order to streamline the testing process for students who take tests through ASAC. Waters also said that the wait times for students to have their accommodation requests evaluated has shortened from three weeks to one and a half weeks on average.

Even so, Aho, Caballero and Medwin all have their own recommendations for improving accessibility in the campus community.

According to Aho, one of the best ways to improve accessibility would be to move toward a universal design model for AU’s campus. Universal design is an approach to accommodations involving seven design principles that are meant to eliminate common barriers to participation for the greatest number of people possible.

“So, to me, the major difference is about shifting that responsibility from the individual student or employee who's disabled or neurodivergent to our larger campus community,” Aho said. “And aspiring to make spaces and events and communities as accessible as possible.”

In the meantime, however, Aho said that improvements can be made by increasing funding for the Center of Diversity and Inclusion, offering hybrid options and American Sign Language interpretation for events, investing in infrastructure and hiring someone whose role is to cultivate disability culture on campus.

Medwin said he feels that creating collaborative spaces for community members with disabilities and centralizing information resources for faculty is a good first step. He also said the campus community would benefit from forming a creative space for people with disabilities.

“Let's have a place where those experiences can be manifested artistically, where they can be done with the freedom of artistic expression,” Medwin said. “Voice is the most important thing.”

Caballero also thinks that community engagement is vitally important. According to her, students need to be further engaged by the University. Otherwise, she said, they run the risk of students with disabilities being left behind.

“As a disabled student, it's very clear to me that I'm not somebody that matters on this campus,” she said.

This article was edited by Abby Turner, Mackenzie Konjoyan and Abigail Pritchard. Copy editing done by Isabelle Kravis, Leta Lattin, Sarah Clayton and Stella Guzik.