A zero in the gradebook can be impossible to overcome. Students who fail are asked to retake classes, meaning they must pay for them twice.

This disproportionately harms low income students. This inequity is exacerbated by harsh grading policies, even in cases of human mistakes or extenuating circumstances. In order to create an equitable learning environment, we must demand institutional empathy and create grading methods that reflect labor.

Calla LaBeau, a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences, was seven hours late turning in the rough draft of their capstone due to their learning disability. The professor’s policy is that late work gets a zero. This meant it was impossible for LaBeau to pass the class with just the assignments on the syllabus.

If a student fails a course required for their major, they must retake it. The Office of Financial Aid told LaBeau that their merit scholarship cannot be extended to extra semesters. Luckily, LaBeau was able to work out extra credit assignments that boosted their grade to just above passing. If not for these extra assignments, granted at the discretion of the professor and help from the department heads, they would have needed to drop their major because they cannot afford to retake the class. LaBeau now faces difficulties in graduate school applications because of the low grade they were given. All because of a barely late assignment, not poor quality work.

Failing a student is a policy choice. AU dictates that performing 70 percent correctly in a class is unacceptable, and professors can create syllabuses that do not account for human situations.

“I work very hard and my GPA reflects that, but I’ve just been having a rough semester because of outside influences, which have made my disabilities flare up,” explained LaBeau.

Strict policies demand the same performance from everyone, communicating to disabled students that their bodies and minds must assimilate to perform well academically. The Academic Support and Access Center falls short of providing equity, by either giving inadequate accommodations or making the process too difficult to get any.

Roughly half of disabled students nationwide receive accommodations, and only 12 percent find them sufficient. As a result, only a little over 30 percent of disabled students complete their degrees.

“It takes me longer to do tasks than peers without disabilities, and it’s oftentimes very difficult to meet deadlines,” said LaBeau. “I have accommodations for flexible deadlines, but sometimes something will happen and I’ll need a [second] extension, and I’m not allowed that.”

It would make much more sense to write empathy into syllabuses, rather than granting it on a case-by-case basis, especially since 45 percent of students would benefit from flexible deadlines.

“I suspect that [strict professors are] going to say something like ‘I’m trying to teach them how the world works,’” said College of Arts and Sciences professor Adam Tamashasky. “It’s an appeal to this fictional punitive world, when … our teachers and administrators have turned things in past deadlines and still have their jobs.”

Lower- and higher-income students can make the exact same mistakes, but these mistakes only jeopardize the careers of those who cannot afford a redo. This disproportionately impacts students of color, as 54 percent of Black students and 45 percent of Hispanic students do not finish their degrees. Uncoincidentally, 51 percent of students who drop out do so because of financial constraints, and Black and Hispanic households have the lowest median incomes in the U.S.

AU financially benefits when students must pay for more semesters. A national survey found that 15 percent of students earn C grades. If this is evenly distributed among the 10 percentage points that signify a C minus to a C plus, that would mean 6 percent of all students earn a C minus. Applied to AU’s enrollment population, that is 859 students. A single credit for a part-time AU student is $1,856 and applying that to AU’s population of 14,318, AU has a potential $4.78 million gain from students who must retake classes.

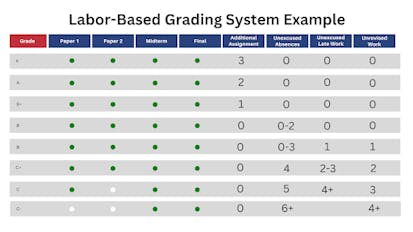

Professors have the power to change this and make classes equitable. Professor Tamashasky has a labor-based grading system.

“You enter into a contract with the students [that] says if you do certain labor, you’re guaranteed a certain grade,” explains Tamashasky. “I didn’t want late assignments to be the reason a student didn’t pass. What matters is that you do the labor and I can respond to it.”

Labor-based grading systems vary between professors, but share the same goal: prioritize learning.

“I used to be the tough-love professor. … I look back and I cringe,” Tamashasky said. “I had the best of intentions. I was trying to help [students] out. But once you see the consequences of the system you use to help them out, you’re not.”

Sociology professor Nicole Angotti implements a labor-based grading system in her classes too. Her syllabus includes two “No-Cost Exceptions,” which can be used to excuse a late assignment or absence, no questions asked.

Labor-based grading systems do not enable a lack of effort. In a survey of Tamashasky’s students, 75 percent of second-generation and nearly 90 percent of first-generation students put more or equal effort into his class than others.

“It’s still AU. It’s still top-tier students doing good work. However, students have said repeatedly that the stress is gone,” continued Tamashasky. “I have seen one concrete difference: students are more willing to take [creative] risks.”

College is meant to be a place of intellectual growth and expertise development. When grading and financial systems make humanity optional, socially disadvantaged students are pushed even farther from success. Labor-based grading systems bring equity to the classroom by providing a proportional reward-punishment system and prioritizing performance improvement.

Greta Mauch is a senior in the School of Communication and an opinion columnist for The Eagle.

This article was edited by Jelinda Montes, Alexis Bernstein and Abigail Pritchard. Copy editing done by Isabelle Kravis, Emilia Rodriguez and Leta Lattin.