For some of American University’s Muslim community, Ramadan has always been about surrounding themselves with family and friends. AU’s Muslim Student Association is committed to building a supportive religious community on campus, which was exemplified in the Ramadan programming facilitated this year by MSA and the Kay Spiritual Life Center.

This Ramadan, MSA leaders wanted their events to be “people’s home away from home,” according to Aseel Osman, a sophomore in the School of International Service and co-president of MSA.

“...This is a lot of people’s first time experiencing Ramadan without their families and fasting by themselves,” she said.

Shahla’ Al-Jawhari, a freshman in the School of Communication, said she feels that MSA has done just that.

“Ramadan at AU has been really nice so far. What’s really nice about it is we have such a big sense of community to the point where you feel like you’re in a family almost,” Al-Jawhari said.

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar and a time for those in the Muslim community to come together to fast, pray and reflect. This year, it fell from March 10 to April 9.

Those who observe Ramadan fast from dawn to dusk, in which they don’t eat, drink, smoke or engage in sexual relations. Suhoor is the pre-dawn meal that begins the fast, while iftar is the breaking of the fast at night.

This year, students observing the fast had suhoor meals provided by AU Kitchen.

“[AU has] been really helpful. They’ve been asking us [for] a lot of feedback, just asking what they could do better,” Osman said.

For iftar, MSA leaders organized programming five days a week. MSA began planning months in advance, which Osman said was crucial. This year, MSA had 15 days to fill with programming, due to spring break falling at the beginning of Ramadan.

Each iftar had its own theme and most were sponsored by other AU organizations, such as Students for Justice in Palestine, the Southeast Asia Student Network and Middle East and North Africa Club. MSA also partnered with other clubs to hold events such as tote bag painting and film screenings.

“We’re under [AU Club Council] … the rules still apply to us having that $3,000 max. But obviously, $3,000 doesn’t feed everyone,” Osman said, adding that programming during Ramadan cost MSA approximately $20,000.

Yet, some members of MSA don’t see money as their biggest barrier. In regards to how AU can assist the Muslim community during Ramadan, Taha Vahanvaty, the co-president of MSA and a sophomore in the School of Public Affairs, said “There's still a lot of work that needs to be done.”

According to Vahanvaty, the biggest need for this community is a “paid staff member” to assist with Ramadan programming. Currently, all of the event planning is organized through volunteer work, mainly by students.

“The food generally brings people together. Like you’re forced to sit with people during iftar. I'm not going to grab my food and leave. No, I grab that food and find my community,” Osman said.

MSA and its members looked at iftar around the world this year, highlighting intrafaith to recognize different sects in the religion.

“The idea has kind of been my passion baby,” Vahanvaty said. “Intrafaith focuses a lot on the fact that, within our Muslim community, there’s so many differences, whether they’re sectarian, ethnic or nationality. We sometimes look over those.”

Vahanvaty describes himself as a “Russian nesting doll” and “a minority within a minority.” He is a Shia-Bohra Muslim, while most of MSA are of the Sunni denomination, he said.

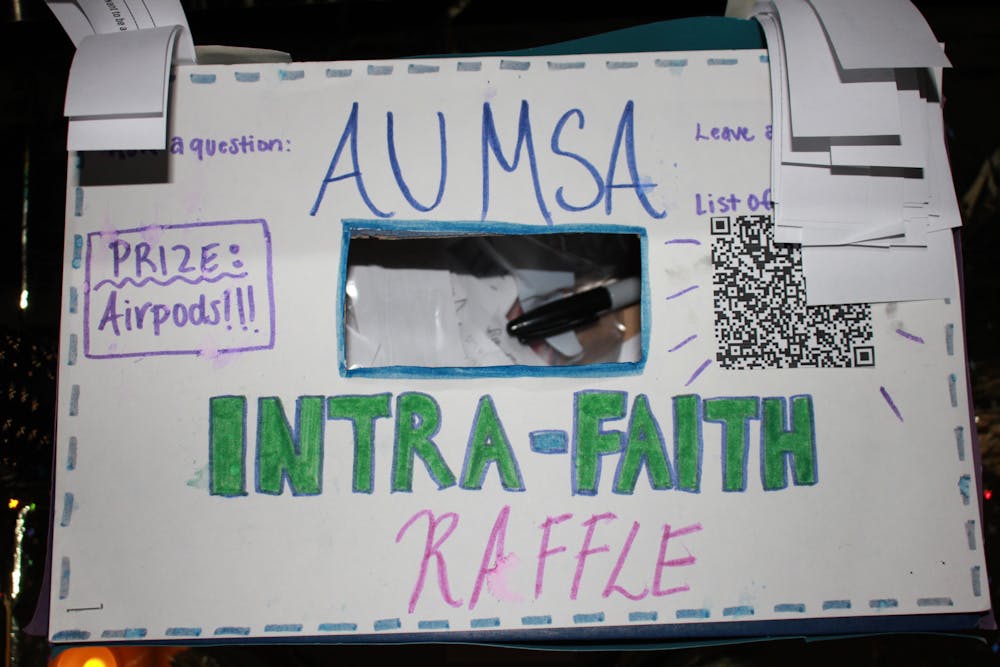

This experience inspired him to champion MSA’s intrafaith project this semester: an intrafaith raffle box. The box allows members to anonymously enter any questions they have about an unfamiliar Muslim community, and each question acts as a raffle ticket for a prize of AirPods. Questions are then uploaded onto a Google Doc, accessible via QR code, where others can anonymously answer the questions.

Vahanvaty said he thinks this anonymity makes the project more powerful.

“Sometimes people get defensive when they’re asked questions [directly],” he said, adding that the box allows for a more open, curious space.

Students in the Muslim community may also face challenges being far away from home. Aatif Mulla is a graduate student in the Kogod School of Business, originally from Bangalore, India.

As an international student, Mulla said it is challenging to not have the support of visiting his family on weekends.

“There’s nobody you can lean on to, but I think that gap has been filled with all the lovely people I have around,” Mulla said, gesturing to the room around him.

He recently spoke with a prospective student from India who is also Muslim.

“I told him it’s much better than what I thought it would be. Everyone’s really warm and welcoming,” Mulla said.

Haniyyah Zia, a freshman in SPA and the outreach coordinator of MSA, said she was worried about being away from her family during Ramadan.

“I think I kind of substituted them with my MSA family … Honestly, I didn’t feel the emptiness that I thought I would,” Zia said.

She added that MSA has created a strong community that provides support for the challenges Muslim students may face on campus.

“I think we all find … that common shared perspective, and the fact that we’re all struggling to be Muslim in a country that is very obviously anti-Muslim,” Zia said.

Continuing with the idea of intrafaith, Vahanvaty said he didn’t see himself in MSA when he first joined. Yet, the community is open to change and new ideas.

“Something that I’ve realized is that there are many houses that are available, but you have to do the work of making a home,” Vahanvaty said. “Unfortunately, the reality of the situation is that that responsibility oftentimes lies on the marginalized. AU is my house. I have to make it a home. That responsibility falls on you, and sometimes that sucks because your entire life … you’ve been going into spaces that are not yours.”

When he didn’t feel represented in MSA, he decided to help lead it.

“When you partake in something, now you’re not just a participant; you’re a creator, which is that concept of creating the homes,” Vahanvaty said. “Homes are only built; they’re not found.”

This article was edited by Samantha Skolnick, Zoe Bell, Tyler Davis and Abigail Turner. Copy editing done by Luna Jinks, Isabelle Kravis and Ariana Kavoossi.