Content warning: This story mentions instances of rape and sexual assault. Please see the bottom for sexual violence resources.

When Melissa Howell’s former professor made sexual and romantic advances toward her on WhatsApp, she brought it to American University’s Office of Equity and Title IX, assuming that it would be what she described as a cut-and-dry case.

Instead, for several months, the Office gave her the impression that it was interested in pursuing an investigation, only to tell her that her professor’s actions did not violate AU’s Title IX policy.

“It was just a complete change in mentality because they seemed really willing to pursue this and investigate it,” Howell said. “And then, they made me literally go into a Zoom meeting that didn’t last more than five minutes just so that they could tell me, ‘Hey, we’re not gonna investigate this. It’s okay. It’s not against policy.’”

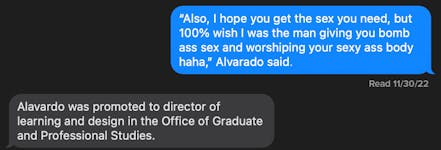

Luis Alvarado, Howell’s former American University Experience professor, sent her explicit messages on WhatsApp near the end of Thanksgiving break in 2022 following Howell’s conclusion of his class.

“Also, I hope you get the sex you need, but 100% wish I was the man giving you bomb ass sex and worshiping your sexy ass body haha,” Alvarado said in a Nov. 30, 2022 message received by Howell and reviewed by The Eagle.

Alvarado was promoted to director of learning and design in the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies in August 2023, according to a LinkedIn profile under his name.

Howell and three other students who spoke with The Eagle about their treatment by the Office of Equity & Title IX said there were severe flaws within the newly combined department that ranged from poor, unempathetic communication to a lack of transparency with the AU community about general Title IX policies.

Students and their advocates at AU have long voiced their concerns with how the Office handles cases relating to sexual violence. With campus-wide demonstrations and walkouts in November 2022, March 2023 and November 2023, some AU students view the administration’s lack of response as disappointing.

“I just really wish Title IX would have been able to do more, or at the very least, been able to tell me at the beginning that a professor trying to have sex with [a] student was not against policy,” Howell said. “I wish they would have just been more proactive and more transparent about the whole situation.”

The Eagle interviewed Howell, who graduated in May 2024, when she was still a student.

In a statement to The Eagle, Matt Bennett, vice president and chief communication officer for the University, said the Office “works with each student to provide comprehensive information,” and that it is never the Office’s intention to provide misleading information.

Insufficient communication with survivors

Title IX is a law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education or in federally-funded programs. Any educational institution that receives federal funding must comply with Title IX, and universities are expected to “take immediate action to eliminate the sexual harassment or sexual violence, prevent its recurrence and address its effects,” according to the Department of Education.

AU’s Office of Equity and Title IX places an emphasis on “fairness and trauma-informed practices for all students, staff and faculty.” The Office seeks to ensure a “transparent and equitable process for addressing and resolving matters of discrimination, harassment and sexual violence.”

The process is designed to be over in a matter of months but usually drags on for several months and even years, according to some students who spoke to The Eagle.

After an incident that occurred in his first year at the University, Ethan Glucroft, now a senior in the School of Public Affairs, reported it to his resident assistant, a mandated reporter.

Glucroft said his first-year advisor, Amanda Getz, was helpful throughout the entire process, especially when the Office stopped responding to his messages.

The Office sent Glucroft emails on March 23, 2022 and April 20, 2022, stating that it could not provide him with any additional, long-term supportive measures regarding his missing work after suffering mental health difficulties.

Supportive measures are free “non-disciplinary, non-punitive individualized services offered as appropriate, as reasonably available” to complainants or respondents, according to the University’s Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy.

Supportive measures are offered before or after a Formal Complaint is filed or if no Formal Complaint is filed.

A Formal Complaint is a document filed by the complainant or signed by a Title IX coordinator alleging a violation of Title IX sexual harassment and requesting that the University investigate the incident. Formal Complaints only apply to instances of sexual harassment, according to federal Title IX policies.

“It is our hope that if there are questions about the implementation of or the details of a supportive measure, the affected student would contact the Office for more information,” Bennett said in an email statement.

As Glucroft continued to email with the Office, he said he received little support and a flurry of automated email responses, eventually resulting in the Office “going back on its word.”

Glucroft said Selena Benitez-Cuffee, the Office’s case manager and hearing administrator, told him in a virtual meeting that what he experienced was classified as sexual assault and that sexual assault doesn’t have to be physical.

Benitez-Cuffee later and formally said that his incident did not meet the definition of sexual assault.

“In your email to Leslie [Annexstein], you mentioned you had to tell your faculty members that you were sexually assaulted. Based on the current report our office has, a sexual assault was not reported to our office,” Benitez-Cuffee told Glucroft in the March 23, 2022 email obtained by The Eagle. “If there is a new incident of sexual assault we would need to discuss the matter further to provide the correct options available to you.”

Because the original incident Glucroft reported didn’t meet the University’s definition of sexual assault, the Office was unable to grant him additional, long-term academic supportive measures related to that specific incident, it told him in an email.

“Based on the lengthy list submitted to our office of missed coursework and assignments, it

appears that you are in need of longer-term academic supports,” an email addressed from the Title IX office wrote on April 20, 2022. “Such longer-term academic supports cannot be provided by the Office of Equity and Title IX in response to the incident you have reported.”

The Office suggested that Glucroft reach out to his academic advisor “immediately for assistance with developing a plan” and told him it would provide him with the supportive measures he “originally requested.”

Two minutes later, Glucroft forwarded the email to Getz, his academic advisor, asking her for help and saying how confused he was with the Office’s inconsistencies. Getz offered her support to Glucroft and admitted she was also confused with the Office’s policies.

“Please don’t apologize for needing support,” Getz wrote in an email that same day. She expressed confusion about “what in the process changed from Monday to today” and said she’d reach out to a case manager for clarification and have her supervisor “reach out to a contact” to see what solutions Glucroft had.

When the Office first began to process Glucroft’s case, he received four emails with automated messages between Feb. 7, 2022 and Feb. 21, 2022.

The first three emails stated that the Office received a report indicating Glucroft was subjected to conduct that violated the University’s Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy and/or Discrimination and Non-Title IX Sexual Misconduct Policy.

The Office offered to meet virtually with Glucroft so it could learn about his experience and provide information about next steps.

The language of the emails frightened Glucroft.

“The whole reason why I was afraid to actually move forward in the first place was because of how unpersonal this was to deal with a personal situation,” he said.

After Glucroft responded to the fourth automated message, Benitez-Cuffee reached out to him on Feb. 25, 2022, and asked him to schedule a virtual meeting at his earliest convenience.

Glucroft responded on March 3, 2022 and apologized for a delayed response due to mental health issues following the incident. He had his first meeting with the Office on March 4, 2022, nearly a month after opening his case, to learn about school resources and supportive measures.

Glucroft and Benitez-Cuffee then coordinated logistics over email about his assignments, what classes he was absent in and specific information about his missing class projects so that the Office could provide supportive measures.

Benitez-Cuffee followed up with Glucroft on March 9, 2022 about her request to send information about his missing assignments. He sent Benitez-Cuffee the assignments on March 11, 2022 and received no response. After still not hearing from his case handler, he sent a second follow-up email on March 16, 2022.

Glucroft then emailed Leslie Annexstein, AU’s assistant vice president for equity and Title IX coordinator, on March 21, 2022.

“I am extremely frustrated and disappointed in the response I received from this office, the whole point of this office is to support me and other students, and the Office has completely failed at that,” Glucroft wrote to Annexstein. “The Office has made it impossible for me to heal, leading me to miss more schoolwork and classes, as I am barely able to function.”

Benitez-Cuffee responded to Glucroft’s second follow-up email on March 23, 2022, exactly a week later.

“Thank you for your patience, I had to unexpectedly be out of the office for the past few days. After conferring with Leslie Annexstein, I wanted to speak with you further to get a better understanding of your needs and confirm the needs of our office to provide the accommodations,” she wrote.

When The Eagle asked the University about its policy when case managers are out of office while actively working on open cases, Bennett said that case managers aren’t responsible for conducting investigations.

“If the case manager is absent for an extended period of time from the Office, another staff member will temporarily perform those job responsibilities,” he said in a statement to The Eagle.

The University lists several circumstances when regular, full-time staff members can take leave from their duties, including in cases of illness, bereavement or change in parental status.

“Annual leave must be approved in advance by the employee’s supervisor and must be taken at times when it will not interfere with the academic, administrative, and/or operational needs of the department,” according to the University’s Staff Personnel Policy Manual.

Glucroft said the Office failed to inform him about Benitez-Cuffee’s temporary absence, and it further damaged his mental health.

Because Glucroft’s experience with the Office occurred during the pandemic when some University operations were online, there was no physical Title IX office he could go to seek answers.

“I pretty much had a mental breakdown trying to find [the physical] Title IX office,” he said.

Students can seek updates about their cases at any time and the University has “internal protocols for providing regular updates to the complainant and respondent in a case,” Bennett said in a statement to The Eagle.

Glucroft said he reached his breaking point towards the end of the process, when Benitez-Cuffee told him in the same March 23, 2022 email that the Office couldn’t provide any additional supportive measures.

“That was the point where I’m like, ‘You gotta be fucking kidding me.’ I’m still actively going through this,” Glucroft said. “My mental health [is] gone, I am spending every day in my dorm because I literally can’t get out of bed because of what I was going through, and at that point, they’re telling me there’s nothing they can do.”

After receiving Benitez-Cuffee’s response, Glucroft sent emails on March 29, 2022, April 10, 2022 and April 17, 2022 asking for updates about the status of his supportive measures. She responded to all three follow-up requests.

In the follow-up email on April 12, 2022, Benitez-Cuffee told Glucroft that her supervisor was out of the office and “signs off on all the documents,” which delayed the final status of his support measures.

Benitez-Cuffee confirmed in an April 18, 2022 email to Glucroft that her supervisor had returned to the office and approved Glucroft’s supportive measures.

Glucroft responded to Benitez-Cuffee’s email and said he had waited over two months to hear back from the Office about whether it sent letters to his professors explaining his academic performance and on the status of his supportive measures.

Instead of healing, Glucroft said he had to “relive this over again” with every professor he told, and, due to the Office’s delays, said he couldn’t make up most of his missing work before the semester ended.

“The Title IX office is supposed to help me, and from my experience it has been a complete failure,” he wrote to Benitez-Cuffee in the same April 18, 2022 email. “How does Title IX propose they are going to handle this with my teachers and rectify the situation that their neglect caused?”

The Office sent Glucroft’s supportive measures that he “originally requested” on April 20, 2022, which included extensions for a few different classes.

Glucroft took an incomplete in his college writing seminar and comparative politics classes and had his grade waived in AUx II, he told The Eagle.

The Office officially closed his case on July 21, 2022.

Similar to Glucroft’s experience, Kimberly Kraska, a senior in SPA and the College of Arts and Sciences, went through a year of back and forth with the Office.

After Kraska’s perpetrator filed a Notice of Allegation against her in January 2023, she filed a cross-complaint through the Office within a week of receiving the notice.

A Notice of Allegation is a written notice provided by a Title IX coordinator to known parties after receiving an initial complaint.

The Office granted her a No-Contact Order on April 10, 2023.

Kraska said her experience with the Office was significantly better the second time. The Office prioritized her case since she knew what protections and services she was entitled to under federal Title IX laws, she said.

Kraska said that despite the Office’s willingness to work with her, its communication efforts were subpar.

If a person is believed to have violated the University’s Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy, a Title IX investigator will interview parties and witnesses, compile and review relevant information and draft an investigative report. Kraska knew this investigative process was vital and wished the Office provided her more clarity when her case was open.

Following the final hearing in her case in October 2023, a hearing panel found that Kraska’s perpetrator “admitted to being a rapist” according to a Nov. 14, 2023, written determination sent by the Title IX office.

The Office is usually required to give a resolution five days after the final hearing, but due to the complexity of her case, it took an extra 22 days, Kraska told The Eagle.

The Office of the Dean of Students informed Kraska and her perpetrator of his sanctions and that he “violated the University’s Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy by engaging in the prohibited conduct of sexual assault (rape)” in a Dec. 6, 2023 document.

Kraska’s perpetrator appealed his sanctions on Dec. 16, 2023, and she was given until Jan. 3, 2024, to respond. After responding to the appeal, the case went to Raymond Ou, the vice president of student affairs.

Kraska was concerned because she knew her perpetrator was “walking around campus” and unsanctioned while she waited for Ou to make a decision about the appeal.

She was frustrated because she knew that Ou, who she said “is not an expert in Title IX, is not an expert in sexual violence,” was the “person was responsible for deciding my fate essentially after I spent already a year going through this.”

Ou received training from the Office of Equity and Title IX at the University, Elizabeth Deal, assistant vice president for community and internal communication, told The Eagle.

Ou also did not respond to the Eagle’s request for an individual comment.

The perpetrator was unsuccessful in his appeal, and the sanctions went into effect on Feb. 14, 2024, suspending him for three semesters from AU’s campus, according to Kraska.

Kraska’s case was closed in February 2024 and remains closed.

Unclear Title IX codes and conducts

A former AUx professor sent inappropriate messages to Melissa Howell, now an AU alum. The Office was initially receptive to her case and told her the different routes and investigations she could pursue, Howell said.

Howell was interviewed while she was still a student at the University, and she took Alvarado’s AUx II class in the spring semester of her freshman year.

Alvarado sent his first text to Howell on Nov. 26, 2022, around or after AU’s Thanksgiving break, she said. Howell was a junior at the time. She said the initial conversation “had no red flags,” and it was casual and professional.

“But then it started to get very, I guess, uncomfortable, is the best word for it,” Howell said. “It started getting more and more obvious that he was hitting on me and trying to start a sexual and romantic relationship with me.”

On Nov. 28, 2022, Alvarado sent a sweaty, shirtless photo of himself from the chest up to Howell. The next day, he made his first romantic advance toward her.

“I mean you’re gorgeous and I don’t really want to deny myself the opportunity to meet people like you,” he wrote in a message obtained by The Eagle.

When Alvarado began pursuing Howell, she didn’t know what to do.

“Honestly, a lot of the time, I was just kind of in denial of it. I really didn’t know how to process it,” she said. “So, that’s kind of why I kept the conversation going. I was just kind of, ‘Oh, ha, ha ha. This isn’t real. There’s no way that a professor could be hitting on me.’”

Howell took Alvarado’s class when she was a freshman and 19 years old. He reached out to her two years later when she was 21 years old and a junior.

She told Alvarado four days later that his advances made her feel incredibly uncomfortable and that it was impacting her academic performance. He apologized later that day.

“Melissa first and foremost I respect you and I always will. I get it that you are not attracted to me and I apologize for taking that chance. You are a wonderful human being with a beautiful mind and I will always think that,” he wrote in a Dec. 3, 2022 message. “You did nothing wrong, I just shared more than I should have. I will never take advantage of you and will always support and want the best for you. I will be happy to continue talking but only if you are comfortable with it.”

But a day later, on Dec. 4, 2022, he made another sexual advance towards her.

“Again you are gorgeous Melissa, so if you were interested of course I’d be thrilled to have sex with you and get to know you in a romantic sense,” Alvarado wrote in messages obtained by The Eagle. “You do know you’re an amazing person right?”

Howell opened her case in December 2022. After she disclosed to a professor that Alvarado had made her uncomfortable, her professor put out a care notice, which is filed when an AU community member notices distressing behavior.

The Office assigned an investigator to Howell’s case on Feb. 10, 2023, and she had her first interview four days later.

However, around halfway through the investigative process, the Title IX office told Howell in an April 12, 2023 email that her case was closed and that Alvarado’s actions did not violate the University’s Title IX and Non-Title IX policies.

The University’s policy prohibits a faculty member from pursuing a consensual sexual relationship with a student or individual who the professor is currently teaching.

The Office said it could only send a message to Alvarado stating that he made a student feel uncomfortable. It did offer Howell an opportunity to take an incomplete in her classes for the semester, which she didn’t accept.

“I thought this would be a fairly open and shut case,” she said. “Especially since I had the support of so many people, I had the support of literally everybody else in my life, except Title IX, the people that should be the ones supporting me through something like this.”

The University’s Title IX and Non-Title IX policies have different definitions of sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is unwanted sexual conduct determined by a reasonable person to be “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive” that it denies an individual access to AU’s educational programs and activities, according to the University’s Title IX Sexual Harassment policy.

Any incidents of sexual harassment falling outside the policy are governed by AU’s Discrimination and Non-Title IX Sexual Misconduct Policy. Incidents of sexual harassment aren’t covered by the policy if the harassment doesn’t meet the previously set threshold of severity, pervasiveness or offensiveness; if it didn’t occur during an educational program or activity at AU or if it occurred outside the United States.

The Faculty Manual, a guide for faculty regarding general university policies and practices, states that “the University prohibits consensual sexual relationships between a faculty member and any student or individual for whom the faculty member has a professional or supervisory responsibility” over.

The Office’s ruling concerned and surprised Howell, especially in a situation where she said Alvarado held, and still holds, a considerable amount of authority over her.

“He works for the administration. I’m still a student,” Howell said when The Eagle initially interviewed her. “In no way is it okay for him to think it’s okay to be hitting on a student and to be having sex with the student.”

Alvarado did not respond to the three email requests for comment the Eagle sent him throughout the investigation, and he did not answer several phone calls when provided another opportunity to comment before publication.

When a faculty member has reportedly violated AU’s Title IX Sexual Harassment Policy or Discrimination and Non-Title IX Sexual Misconduct Policy, the Office reaches out to the potential complainant and offers them an opportunity for an intake meeting, Bennett told The Eagle.

“During the intake, facts are gathered about the matter to determine whether the alleged conduct falls within the jurisdiction of either non-discrimination policies and to discuss the resolution options, supportive measures and available resources,” Bennett said. “If the complaint falls within the jurisdiction of one of the policies and an investigation is requested, an investigator is assigned to the case and a notice is issued that informs both parties of what is being investigated.”

Georgetown University’s Policy on Sexual Misconduct explicitly states that relationships between staff and students are strictly prohibited, regardless of whether the professor currently teaches the student.

The policy emphasizes the power imbalance when sexual harassment occurs between “teachers and students or supervisors and subordinates,” writing that “sexual harassment unfairly exploits the power inherent in a faculty member’s or supervisor’s position.”

Under Howard University’s policy, “sexual or romantic relationships, including dating, between students and faculty, staff, or any other type of University employee are strictly prohibited.”

AU’s Faculty Manual, however, permits faculty, staff and students to have sexual relationships so long as the faculty member holds no “professional or supervisory responsibility” over the student or individual.

While the University’s policies don’t explicitly state the power imbalance between faculty and students, it does require faculty members to “disclose and to eliminate any conflict of interest that can potentially undermine the trust on which the educational process and employment environment depend.”

Callous interactions with survivors

Mari Santos’ resident assistant requested a room change for her on Oct. 17, 2022, during the fall semester of her freshman year. She reported that a resident in her dorm would often show up to and enter her room uninvited. His behavior became so disruptive that she had to sleep in her friend’s room to mitigate interactions with him, she told The Eagle.

Santos sent emails to a community director asking to have her room change expedited, and there was “official talk,” she said, on Oct. 28, 2022, about processing her request. AU’s housing department granted her a room change on Oct. 31, 2022, and she moved into her new room on Nov. 1, 2022.

When Santos tried to seek protective measures, Fariha Quasem, her case worker, told her in a virtual meeting that the Office couldn’t file a No-Contact Order because the person in her residence hall didn’t physically harm her. Quasem no longer works for the University.

“As I said during our meetings, our office will not be able to provide you with a No-Contact Order,” Quasem told Santos in a Nov. 10, 2022, email obtained by The Eagle. “I explained that we would not be able to provide the order because what you had shared was not a potential violation of our policies. Additionally, we cannot provide you with an order because you believe he will contact you in the future.”

Quaseum didn’t respond to the Eagle’s request for comment.

A No-Contact Order is a supportive measure granted by the Title IX office to mitigate future contact between individuals that would violate AU’s Title IX or Non-Title IX policies. In order for the Office to grant an individual a No-Contact Order, they must “allege a potential violation” of both policies, according to a Title IX information sheet.

“I cried to my friends afterward and I said, ‘I wish he would physically touch me so I can get this over with and finally find peace.’ Which, looking back, I can’t even — Jesus Christ,” Santos said.

However, Deal, when asked under what circumstances the Office would deny an individual’s request for a No-Contact Order, said that “contact is defined broadly and is not limited to whether the individuals had physical contact.”

Deal’s statement contradicted Quasem’s reasoning for why the Office denied Santos’ request for a No-Contact Order.

Santos first interacted with the Office on Sept. 27, 2022, after her resident assistant reported an incident on her behalf. She told it through email that someone in her dorm asked frequent, invasive questions about her race and religion.

Eventually, the person’s behavior became more disruptive to her, and the Office told her in a virtual meeting that it would follow up with her about her concerns but never did, Santos told The Eagle.

“They said they would contact me within the next week, and I gave them three weeks, and nothing happened, so I just assumed I got ghosted by the Title IX office,” Santos said.

And when someone on Santos’ floor moved out, she realized that a room change was “the only solution” to her situation. Her resident assistant reached out to a community director and requested that he expedite the process because the situation was serious.

She expected to move into her new room that Friday on Oct. 28, 2022, but when Friday came, she didn’t receive any updates. When Santos saw the community director that evening, she said that he “shrugged her off” and told her that she’d have to wait until next week to file a room change request because the housing portal closed on Friday.

“I had a housing complaint, so this is your job, man,” she said in an interview with The Eagle. “And so I just felt extremely disrespected. I was angry.”

Afterward, she emailed the community director and his boss, who no longer works at the University, demanding that she receive the empty room. The community director said that because she spoke with AUPD, her case was redirected to the Office.

When asked about Santos’ statements about the community director, his former supervisor and Quasem, the University said it could not comment on individual matters.

Santos was officially granted a room change on Oct. 31, 2022, and moved in the next day. However, the resident who harassed her found her room on Nov. 2, 2022, the day after she moved in.

After informing the Office of this, Santos emailed a week later and asked for an update, and Quasem said the resident in her dorm refused to meet with the Office. On Nov. 17, 2022, Santos received an email from the Office stating that he agreed to leave her alone and never speak to or go near her again.

The fight to change rooms took a severe toll on Santos’ mental wellbeing, she said.

“But it took me everything in my power. I was the reason I got what I wanted, not Title IX, not the housing department. It was me,” Santos said. “Because I shouldn’t have to email, email, email everyone begging for stuff when this is [the Office’s] responsibility. On top of handling schoolwork, on top of just handling my life in general and then having to live in these conditions. I shouldn’t have to deal with that.”

Like Santos, Kraska –– who has had two separate experiences with the Title IX office –– said that the Office’s poor communication efforts burdened and required her to frequently follow-up through email about the status of her cases.

In Kraska’s first experience with the Title IX office, an individual implicitly threatened her life in late January 2022. The person in Kraska’s first interaction with the Office is different from the person involved in her second interaction with the Office.

Kraska first interacted with the Office when she spoke with Jaris Williams, who was the associate dean of students and director of inclusion support, on Feb. 8, 2022. Williams no longer works at AU.

The Office of the Dean of Students issued Kraska a No-Contact Order on Feb. 18, 2022, and the Title IX office issued another No-Contact Order to replace the one from the Dean of Students on March 2, 2022. Kraska received her notice of investigation on March 16, 2022.

The Office notified Kraska of its decision exactly six months after she first contacted Williams, and it found the respondent not responsible for stalking and dating violence.

Without consulting her schedule beforehand, the Office told Kraska on July 13, 2022, that her hearing would occur on July 28, 2022, she said. But, she couldn’t attend the hearing because of a family vacation. Benitez-Cuffee told Kraska in a July 15, 2022 email that the hearing could not be rescheduled.

Annexstein also told Kraska that the respondent, three panelists and the advisor “cleared their schedules and made themselves available on July 28” and that Kraska was disengaged with the process.

“I do not see a communication where you have provided an end date for your vacation,” Annexstein wrote in a July 25, 2022 email obtained by The Eagle. “This, coupled with the fact that you have not engaged in the process to review the investigation report that will be presented at the hearing, has signaled to our office that you have disengaged from the process.”

Annexstein offered to reschedule Kraska’s hearing to the best of her ability but warned it would cause the Office to further delay her complaint’s resolution.

Kraska responded that same day to Annexstein’s email, asking the office to be “considerate of how long and mentally taxing this process would be for a 19 year old student” and that she didn’t intend to seem disengaged with the process.

“I was crying in my mom’s arms as I wrote this,” Kraska wrote in a June 5, 2024 email when she shared the documents with The Eagle. “I could not believe that the people at the Title IX Office, the Office that I was supposed to feel comfortable reporting disturbing behavior from a past intimate partner, were treating me like I was being ungrateful for all they had done for me.”

After some back and forth, Benitez-Cuffee informed Kraska in a July 27, 2022 email that her hearing was rescheduled to Aug. 4, 2022. This confused her more, since “if anybody can know that Title IX hearings can be rescheduled, it should be the hearing administrator,” Kraska said.

Annexstein and Benitez-Cuffee declined the Eagle’s request for comment regarding their interactions with Glucroft and Kraska and deferred to the University’s communications department.

The Eagle reached out to every individual employee in AU’s administration named in the investigation.

“The University maintains the confidentiality of information that is shared with the Office of Equity and Title IX and disclosures are limited to those persons necessary to process in addressing the concern,” Deal wrote in a Nov. 13, 2024 statement. “Therefore, the University does not provide public comments on any individual matter that may have been presented to the Office of Equity and Title IX. Additionally, the Family Educational Rights Privacy Act (FERPA) protects student records.”

Kraska was first interviewed in April 2023. The Office’s interest in her second case diminished as it stretched into the summer, she said in a September 2023 follow-up interview.

Kraska’s investigator –– who she said treated her better than any other employee in the Office –– promised to update her every two weeks, regardless of whether the Office had made progress in the investigation.

The first time Kraska followed up with her Title IX investigator after not receiving an update, she apologized and said the Office made no progress. Kraska emailed her Title IX investigator on July 7, 2023, and said she hadn’t received a status update in over three weeks.

Her investigator responded and said that while the timeline was unclear for when she would receive a preliminary report, the report had reached the finalization and editing stage.

“Thank you very much for your patience; I truly appreciate it,” Kraska’s investigator wrote.

Students’ demands for the University

Lillian Frame, who organized several protests that condemned the administration’s response to sexual violence, repeatedly criticized AU for how it handled sexual harassment and assault on campus. Despite the University’s heavy emphasis on equity, equality and treating students fairly, it follows through with “absolutely none of it,” she said.

“AU’s Title IX office is a true example of what I think can be the worst of Title IX offices,” said Frame, who graduated from AU in 2023.

Frame worked with Know Your IX, End Rape on Campus, It’s On Us and SafeBAE, organizations that combat sexual violence and empower survivors. In her time at AU, she offered support to survivors and frequently lent her expertise to individuals navigating the Title IX process.

The University launched the Community Working Group on Preventing and Responding to Sexual Harassment and Violence in November 2022 after a break-in and sexual assault in Leonard Hall, which spurred campus-wide protests.

Former President Sylvia Burwell tasked the group to ease and respond to students’ concerns and ensure that the University’s sexual violence prevention information and resources were accessible and updated.

In March 2022, the AU Undergraduate Senate unanimously passed the Survivor’s Bill of Rights, which entitles survivors to protections like updates within three business days regarding their complaints’ outcome, fair access to all available medical resources and the right to hold “all university” entities accountable if they don’t grant survivors protections detailed in the bill.

AU’s Undergraduate Senate does not have the power to enforce these bills unless the University decides to implement the changes itself.

Frame and Emily Minster, a survivor advocate who also graduated from AU in 2023, organized a campus-wide walkout in protest of sexual violence and “administrative ignorance” in November 2022.

Frame wrote in a November 2022 email to The Eagle that the Office’s violations were timelines of cases, what constitutes harassment, how reports were filed, “lying to students” and “what it takes to get a No-Contact Order or other accommodations.”

“I’ve had a survivor tell me that the Office told her that unless something physical happened to her, they couldn’t report it,” Frame said. That survivor was Mari Santos.

Minster, who completed her bachelor’s degree in SPA and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in political communication from AU, also noted the Office’s procedures fell short on multiple levels.

“I think that for the most part, it seems like people have good intentions, but there’s a lack of capacity to address everything that needs to be addressed,” she said.

It’s challenging for survivors to get answers about accommodations because the Office doesn’t “always know the answers,” Minster said. It’s also difficult for survivors to receive adequate counseling and support because the Office “doesn’t know who to refer to,” she said.

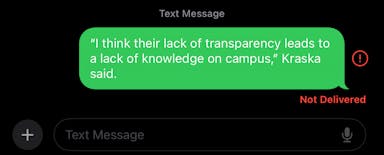

When survivors don’t have an informed support system, the University willfully chooses not to follow guidelines “when they can get away with it,” Kraska said.

“I think their lack of transparency leads to a lack of knowledge on campus,” she said.

Students who have experienced sexual violence can reach out to Victim Advocacy Services, the Center for Well-Being Programs and Psychological Services or these hotlines for guidance and support:

- National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-4673

- Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) Hotline: 1-800-656-4673

- D.C. Rape Crisis Center: 202-333-7273

Additional resources:

- It’s on Us

- Know Your IX

- End Rape on Campus

Editor’s note: Mari Santos is an opinion columnist for The Eagle. She was initially interviewed for this story before joining the opinion section in Spring 2024. Per The Eagle’s ethics code, opinion writers are not allowed to write for the news section and are permitted to promote or criticize a particular point of view on issues that The Eagle is covering. Santos was not involved in the pitching, writing or editing of this story.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly said American University’s Undergraduate Senate does have the power to enforce bills. It has been corrected to reflect that the senate does not have the power to enforce bills unless the University decides to implement the change itself.

This article was edited by Mackenzie Konjoyan, Walker Whalen, Tyler Davis, Abigail Pritchard and Abigail Turner. Copy editing done by Luna Jinks, Ella Rousseau and Ariana Kavoossi.