From: Silver Screen

“Concrete Cowboy” tackles father-son relationships and community in a unique setting

Ricky Staub’s directorial debut, “Concrete Cowboy,” tells the age-old story of familial reconciliation in a not-so-common setting.

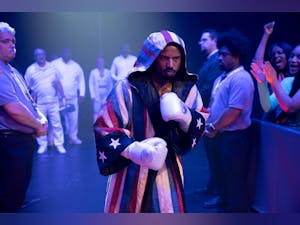

The film follows the relationship between Cole (Caleb McLaughlin), a 15-year-old inner-city trouble maker, and his estranged father, Harp (Idris Elba).

Upon Cole’s expulsion from school in Detroit, his mother, Amahle (Liz Priestley), drops him off at Harp’s house in an urban part of Philadelphia for the summer. Cole is dismayed to find his new home in terrible condition, containing nothing but beaten-up furniture, a fridge filled solely with soda and old beer and Boo, one of the many horses that Harp takes care of with his team at the Fletcher Street Urban Riding Club. A fed-up Cole leaves Harp’s place to go hang out with his cousin, Smush (Jharrel Jerome), who we quickly learn deals drugs.

Throughout the rest of the film, we watch Cole’s journey as he decides whether to follow in Harp’s footsteps or run with Smush. Eventually, he will choose the former option.

“Concrete Cowboy” ends with a reunion between Cole and his parents as they all embrace each other for the first time in years.

All in all, the film is predictable. Smush fulfills the tried and true narrative of the inner-city kid who couldn’t quite make it out of his environment in time, (think “Boyz n the Hood,” “Menace II Society,” etc.) and “Concrete Cowboy” has no problem embracing it.

Equally as predictable is the family reconciliation at the end of the film. From the get-go, we can tell that Cole and Harp will eventually bond with each other. And while this may be intentioned as heart-warming or redemptive, it largely comes off as trite.

While the reunion is easy to spot, it’s also forced. There’s no logical progression from estrangement to reunion; the script simply insists that they must learn to like each other.

The film does have its merits, though. Elba’s grizzled, “I’ve-seen-some-stuff-in-my-day” delivery is aptly paired with his cowboy persona. His do-it-yourself attitude and the cigarette that never seems to leave his mouth hearkens back to the classic outlaws of old Westerns.

Staub’s direction also shows flashes of brilliance. He uses the camera masterfully to elicit visceral feelings in the audience.

During the moment before Smush’s demise, we watch through Cole’s eyes as his cousin walks up to the front of the gas station where the deal is to go down. There’s a quiet calm-before-the-storm buildup to the shooting, as we are forced to look on in silence, as helpless as Cole is to stop the inevitable. The camera suddenly fades to black. Gunshots blare out at high volume, and we’re jolted right back into the scene with a force via a shaky POV shot that follows Cole running towards the crime scene.

We feel the full emotional impact of the situation no matter how certain the outcome was. No amount of foresight can prepare us for sudden loss, and the frantic camera movements combine perfectly with distorted street sounds to capture that feeling.

“Concrete Cowboy” is far from a perfect film. Its results are expected and its story is nothing new. Yet we can’t help but feel emotionally drawn to the characters’ performances and the story’s oddly enticing Western mystique in the midst of Northern Philadelphia.

Deep down, we all want to ride off into the sunset just as Cole and Harp do, together.